Las Vegas is set to host the FIA Formula 1 World Championship later this week. This impending half-billion-dollar gamble isn’t the first time that the Grand Prix circus has visited the Entertainment Capital of the World. Unlike the state-of-the-art facility awaiting today’s teams, F1’s original two-year foray to the casino oasis was spent in the parking lot of Caesars Palace.

The early 1980s for Formula 1 was similar to the present in many ways. The championship’s then-commercial czar Bernie Ecclestone had massive aspirations to expand the race schedule to lucrative new markets. In the midst of the Cold War, he envisioned running street circuit races in the capitals of communism and capitalism. Yes, Bernie wanted F1 to race in Moscow under the shadow of the Kremlin and around the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers in lower Manhattan.

Ecclestone’s push into the American market was already underway with two races. The United States Grand Prix was an established event held at Watkins Glen in upstate New York every October since 1961. The Long Beach Grand Prix joined the calendar in 1976 as a Southern Californian version of Monaco. Both events offered entertaining races but struggled financially and owed money to F1. Enter Caesars Palace.

Las Vegas was the fledging fight capital of the world. The formula was simple yet profitable for casinos. Marquee boxing bouts held at relatively small on-site arenas attracted big spenders who filled luxury suites, bought expensive tickets and placed massive bets. The fight itself also promoted the casino to help organize the next bout and repeat the cycle.

Caesars Palace pushed this formula to its absolute limit in October 1980. The Roman Empire-themed casino hosted “The Last Hurrah!” which would be the penultimate fight of Muhammad Ali’s boxing career. Ali would challenge his sparring partner Larry Holmes for the world heavyweight championship. With their existing venue unable to satisfy demand, the casino built a temporary 24,790-seat outdoor arena in its parking lot.

The event itself was grotesque. Ali’s health was already declining. The 38-year-old had trembling hands and other symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, a diagnosis that he would make public a few years later. According to BoxingRec, Holmes landed 340 punches in the 89-degree heat. Ali landed just 42. The fight was stopped after the tenth round.

The balance sheet told a completely different story. Caesars Palace made $5,766,125 in gate revenue, a then-record for boxing. The most expensive ticket cost $500, or about $1,860 in today’s dollars. Ali-Holmes ended up just the start of big outdoor bouts at the Palace. The casino had eyes on expanding outside of boxing.

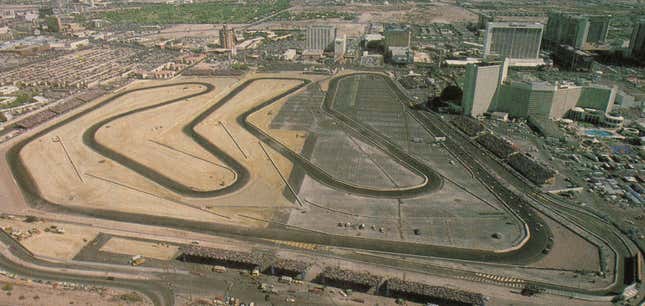

Caesars Palace decided that Formula 1 would be the perfect follow-up event to host in October 1981. The casino brought in Long Beach Grand Prix promoter Chris Pook to organize the new race. The only problem was setting up a racetrack within the confines of the parking lot. The casino property was hemmed in by the Strip to the east and Interstate 15 to the west. The track could extend north to a small patch of empty land but nothing more.

The circuit had to dart back and forth across the lot to meet the minimum length for F1 courses. The freshly laid surface was exceptional, but it couldn’t plaster over the “Mickey Mouse” feeling many drivers had going around it. The counter-clockwise direction, common for American ovals but nearly non-existent for F1, put added strain on the drivers’ necks. Also, no garage structures were built to shield the teams from the desert sun.

F1’s problems aside, the inaugural race didn’t sell out and failed to be the draw that Caesars Palace hoped it would be. After an unsuccessful second attempt, IndyCar tried its hand to bring a crowd to the casino and also left two years later.

While racing had failed, Caesars Palace pushed on with outdoor boxing matches through the 1990s and experimented with other sports in the parking lot. The casino hosted a preseason National Hockey League game in 1991. The matchup saw Wayne Gretzky and the Los Angeles Kings beat the New York Rangers on a temporary ice rink. The World Wrestling Federation even held Wrestlemania IX outdoors at Caesars Palace in 1993.

As time passed, the biggest boxing cards moved to casinos with newer and larger indoor arenas like the MGM Grand and Mandalay Bay. The storied parking lot was eventually replaced with the Forum Shops, a luxury shopping mall. Ultimately, the only thing that matters in Las Vegas is the revenue generated from patrons. Everything else is a means to an end.