I just crawled under the 2020 Land Rover Defender—the unibody, independent suspension-equipped successor to a legendary body-on-frame, solid-axle off-road brute. What I saw didn’t appear to be an SUV built on a special off-road platform, but rather a machine quite similar to other vehicles in the Land Rover lineup.

This isn’t a bad thing, nor is it particularly surprising—Land Rover has the tooling and supply chain to build aluminum unibody vehicles with independent suspensions, so it makes sense for the company to use that capability to save on cost. Still, the die-hard Land Rover Defender fans who were hoping for a totally unique off-road workhorse built on a special off-road platform like the legendary Defender of yore might be a bit disappointed. (For the record, Land Rover says the Defender’s “D7x” platform is new, and that the “x” stands for “extreme.”)

We’ll make some use of comparative slides in this post, so look out for arrows you can click when pictures are stacked.

Let’s get straight to the underbody, peeking under the two-door Defender 90 from the front of the vehicle looking rearward:

I was surprised to see that, instead of giant sheets of heavy steel or even aluminum skid plates, the belly pan appeared to be made of a fibrous material, not unlike the aero covers that you might find under sedans, crossovers, and pretty much any type of modern vehicle. Here are a few other angles:

Though it’s clear that Land Rover has tested this Defender quite a bit off-road, at least by the looks of it, that fibrous material—held in place by a number of small bolts—doesn’t appear particularly tough (especially not resistant to bending), and I’d be concerned about it holding dirt and moisture or possibly tearing, as it sits quite low under the rocker panels:

Here’s another look, along with a view of an aero “spat” apparently meant to deflect air around the rear wheels:

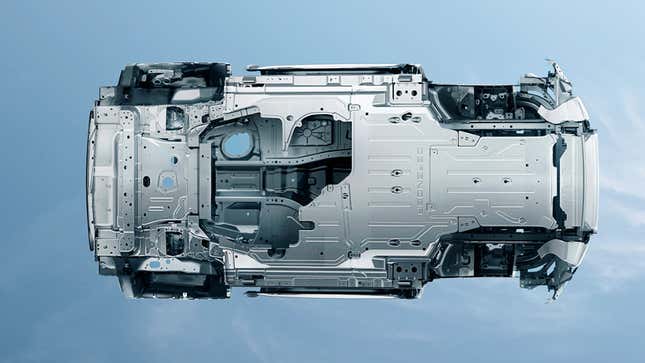

Update: As reader ThatJeepGuy pointed out in the comments, Land Rover’s website includes the image below, which indicates that these fibrous belly pans are actually fastened to quite a bit of underbody armor. Fibrous pans still seem a bit out-of-place for an off-roader, but it’s good to know that they don’t appear to be tasked with protecting hardware. I’ve reached out to Land Rover to learn more:

One thing I have to give Land Rover lots of credit for is how its engineers were able to tuck much of the drivetrain—especially the two-speed transfer case and front and rear driveshafts—so high up. Look at the underbody images above, and you’ll be hard-pressed to catch a glimpse of the transfer case or driveshafts.

What you will spot, especially when looking from the rear, is an exhaust pipe:

But even that is tucked reasonably high up into the body, except at the rear where it drops down below the axle and around the apparently-aluminum automatically locking rear differential, which—you’ll notice below—sits low and looks to be almost completely unprotected:

Here’s a closer look at that diff, except this time on the four-door 110 model:

That differential case, by the way, looks quite similar to the one found in the Range Rover shown below:

And the seven-passenger Discovery’s diff looks similar, as well:

While we’re back there, we may as well have a look at the suspension, which, on the Land Rover Defender, is an integral link setup with air springs—the same suspension type found on the current Land Rover Discovery. And, in fact, if you compare the two, as I did on the Frankfurt Auto Show floor, you’ll notice quite a few similarities. Here’s some comparison between the rear suspensions across Land Rover’s lineup:

From the front, here’s how the Defender’s rear suspension looks. Since everything was a bit tight, we’ll have to use two images.

First, let’s compare control arms from the same angle:

Here’s another perspective from the front side of the rear suspension showing the cradle mount, another suspension link, and the strut.

Now let’s take a look at the front suspension, which is an SLA short long arm style double wishbone suspension. Here’s a look at the passenger’s side (left side) front suspension as viewed from the rear:

Viewed from the front, here’s a look at the left side front suspension:

If you’re wondering whether the suspensions share parts, it seems that the answer is “yes.” Let’s first look at the front suspension’s upper control arm design of the Discovery and Defender (I didn’t get a good shot of the Range Rover), starting with the latter as viewed from behind the front axle:

And here’s the Discovery, but on the other side of the vehicle. By now it should be clear that the two front suspensions look largely the same:

Peeking at the suspension from the front of the vehicle, I can get a glimpse of the part numbers on the upper control arm:

Both parts have the text “EZB6A” and “PLA-3091-A” cast into them, with the latter number seeming to align with the part number of upper control arms found on older Range Rovers.

The same goes for the right side of the vehicles, where the upper control arms share the number “PLA-3084-A.”

I’ll reiterate that parts sharing isn’t a bad thing, and as I’ve stated before, the Land Rover Discovery is actually pretty damn solid off-road. Still, though sharing a common suspension design will undoubtedly yield a more refined and better-handling vehicle, it also hurts articulation potential (especially with sway bars disconnected), as press images like the one below show:

When traversing off-road terrain, you want your vehicle to have as many tires on the ground as possible to maximize grip. Independent suspensions with short control arms, like the design on the new Defender, simply don’t allow much flex, and the result is tires lifting off from terra firma.

Many modern SUVs, including Land Rovers, compensate for this with traction control carefully regulating the application of power to wheels that stay on the ground. But still, the more wheels that can bite dirt, the more grip you’re going to get.

The setup is also, at least traditionally, considered less robust than a solid axle, and what’s more, it’s definitely more difficult to lift, in part, because the angles of the constant-velocity joints (the things inside the accordion-looking rubber boots on the axle shafts) could get too steep and prematurely fail. So don’t expect to see lots of new Defenders modified to this extent:

I will admit that there were very few other mechanical bits that I could spot under the Defender, since so much was covered by fabric aero pans. Still, in general, two good ways to tell how much platforms have in common is to look at the suspension and its mounting points, including the strut towers. Here’s that of the Discovery:

You’ll notice a similar shape to those strut towers, as well as similar fastening methods for the strut braces:

Road & Track wrote back in August that the Defender and Disco would share platforms, so really, these revelations aren’t particularly surprising, but they do confirm a clear shift in the Defender’s priorities from outright off-road capability to on-road refinement.

There are a few other off-road-related things that I noticed when I saw the Defender up-close. For one, there’s quite a bit of low-hanging plastic, particularly at the bottom of the front bumper (though this vehicle is likely not sitting at its highest ride height):

It is worth mentioning that Land Rover does offer a five millimeter-thick aluminum skidplate that appears to at least protect the center of the bumper:

There’s also quite a bit of painted plastic on the rear bumper, though that overhang is short enough and high enough off the ground that I wouldn’t be so concerned:

Speaking of overhangs, that’s an area where the Defender is particularly strong, which is good, because the single most important attribute of any off-roader is geometry. The Land Rover Defender 90, when equipped with air suspension and set to maximum ride height offers 11.5 inches of ground clearance, an approach angle fo 38 degrees, a departure angle of 40 degrees, and a breakover angle of 31 degrees. The four-door 110 model shares those angles, but drops the breakover figure to a still-respectable 28 degrees.

In comparison, a Jeep Wrangler Rubicon’s approach angle is about 44 degrees, its departure angle is 37 degrees, and its breakover is 27.8 degrees for the two-door and 22.6 degrees for the four-door “Unlimited” model. Ground clearance is 10.8 inches.

So even compared to the Jeep, the Defender’s numbers are phenomenal. Though it is worth mentioning that, just as important as overall ground clearance figures, is where that clearance is. I’d be curious to see how the ground clearance of the two vehicles compares at the rocker panels and at other points between the front and rear axles.

Just as important as those angles is overall vehicle size and weight, and in those areas, the Land Rover seems a bit huge. At 180.4 inches long, 78.6 inches wide, and 77.5 inches tall, the Land Rover has over a foot on the Jeep between the front and rear bumpers, plus it’s 4.8 inches wider and 3.9 inches taller. The four-door 110 model is 197.6 inches long, or over nine inches longer than the four-door Wrangler Unlimited.

But it’s not just exterior dimensions where the British off-roader’s numbers dwarf those of the Jeep, it’s also weight. The Defender 90 weighs 4,830 pounds despite having an aluminum body; the two-door Jeep sits at a maximum of 4,222 pounds. The lightest four-door 110 weighs about the same as the 90, but it’s still over 330 pounds heavier than the heaviest four-door Wrangler.

Still, despite size and weight, the plastic lower front fascia, the fiber(ish) belly pan, and the clearly Land Rover Discovery-based suspension setup that doesn’t appear to offer much articulation, I bet the Land Rover—aided by great ground clearance, short overhangs, an air intake system that lets the Defender wade nearly three feet of water, big 32-inch tires, what appears to be decent underbody armor, and a locking center and rear diff, will kick butt off-road. Will it ever be the legend that its predecessor was? Maybe not, in part, because its aluminum unibody and independent suspension probably won’t take well to heavy modifications like solid-axle swaps or lift kits.

Still, I love the way the new Defender looks (aside from that hideous fake pillar on the short-wheelbase model). It’s upright, squared-off, and, especially with the air suspension at full ride height, it just looks rugged. From underneath, less so, but again, none of this is a surprise. This Defender comes with 18 to 22 inch wheels, after all.

Update, September 14, 2019, 6:13 P.M. ET: This story has been updated with an image and with text to mention what appear to be skid plates under the fibrous sheets coating the Defender’s underbody.