FLINT, Mich.—Before its faucets ran brown, before its residents were poisoned by lead, before it was Murdertown USA, Flint, Michigan was Vehicle City.

Everyone in Flint has a story about General Motors. Flint is where GM was born more than 100 years ago. It rose a GM company town, home to scores of car plants in the area over the decades. It boomed in GM’s earliest years before World War II, saw the creation of the modern auto labor movement, and for decades was a place where working class people could find good-paying jobs.

But Flint fell alongside GM too, both as plants closed and jobs moved overseas and the city’s own tax base eroded when GM moved outside Flint proper to its suburbs—moves subsidized by Flint itself for the sake of its largest and most vital employer. In building a city around GM to thrive, Flint laid the foundation for the conditions of the city’s water crisis—which began three years ago this week—to explode.

And emails obtained by Jalopnik through open records requests show GM’s water problems were far more extensive than previously disclosed, including issues at its assembly plant in the city that have gone unreported until now.

Gladyes Williamson has stories about GM too. The 63-year-old Buick retiree’s stories are about how her Flint house is now nearly worthless, how her hair fell out, and how her own grandchildren won’t come see her anymore for fear of being poisoned.

“This is about poverty and the working class man, and this is about General Motors leaving Flint in a catastrophic situation that caused all of this,” she told me in a recent interview.

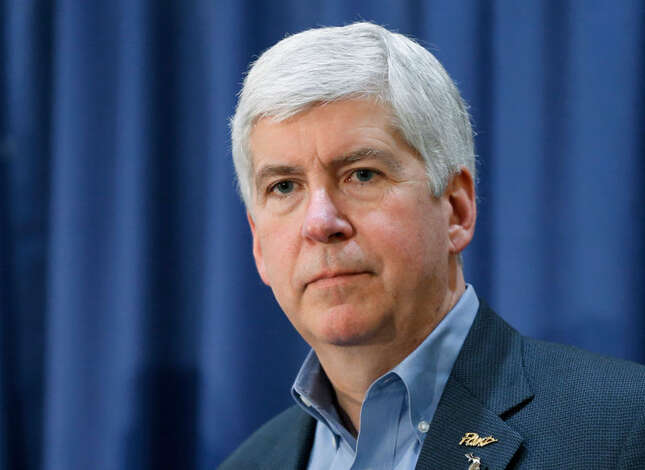

In 2011, with Flint, Michigan in a financially precarious place, Gov. Rick Snyder appointed someone to run the Rust Belt city, usurping its democratically elected officials through a state law that gave him the power to do so. That appointee, direly called an “emergency manager,” decided to save money by switching the city’s drinking water source from Lake Huron to the highly corrosive Flint River as a temporary measure to save about $2 million annually.

The plan, however, was haphazardly organized. Regulators didn’t properly treat the water, thereby allowing the corrosive river to leach lead off water service lines and taint the supply by the time it reached homes across the city.

You’ve probably heard that story. At this point it’s hard not to be at least somewhat familiar with the Flint water crisis.

Here’s a story you may not have heard: in May 2014, just weeks after Michigan switched Flint’s drinking water source to the polluted river, a significant problem had emerged at GM’s facilities in town.

The same water supply wreaking havoc on people’s lives—rancid odors, abhorrent discoloration, high levels of bacteria, and a god-awful taste—was also corroding parts at GM’s engine plant in town and causing significant issues at the automaker’s nearby assembly factory.

For GM, the water at its engine factory had become so problematic by October 2014 that it successfully persuaded officials to allow it to switch back to the previous source, the one provided by the city of Detroit. (GM’s assembly and stamping plants in town reportedly stayed on the Flint river, despite noticeable issues at the assembly plant.)

Yet according to GM, throughout 2014 it never tested the quality of the water—reportedly used for drinking water, coffee and showers—at the taps of its Flint operations.

When asked, the company refused to say why. A document sent by a spokesperson noted that it tested “consumable water sources” at its facilities, but not until the fall of 2015, when the situation proved even worse and it emerged that lead was leaching off water pipes and flowing into the Flint water supply.

And so as residents were dealing with a boil water advisory over high total coliform bacteria levels and brown water spewing from their faucet, city officials quickly acquiesced to the automaker and allowed it to leave the system, emails and documents show.

GM got off easy while residents’ complaints fell on deaf ears. It would be another year before Flint switched back to its original source, when the Snyder administration finally admitted there was also a lead problem.

In a city whose highs and lows are deeply intertwined with GM, the optics were jarring.

There’s an untold side to GM’s recent role in Flint—apart from the common tale of lies, cover-ups, and an environmental nightmare that has led to criminal indictments of 13 state and local officials. The auto behemoth didn’t have a direct hand in the governmental decisions that led to Flint’s water becoming tainted with lead, but GM figures into the complicated situation of Flint’s water crisis, whether it wants to admit it or not.

Years of dumping from the auto plants contributed to the pollution in the river. And as GM drastically reduced its Flint footprint over time—starting in 1940s with the opening of eight industrial complexes, all in Flint’s suburbs rather than in the city—the city’s tax revenue evaporated in tandem.

It’s interwoven with longstanding issues of race and the impact of deindustrialization, as documented in a lengthy report issued in February by the Michigan Civil Rights Commission.

While GM says it has since donated millions of dollars to support community programs for children affected by exposure to lead and causes like United Way, when pressed for specifics on timing, the automaker comes up light.

“When GM learned of the health advisories regarding Flint’s drinking water it promptly took steps to test water at its Flint operations and to install water filters where appropriate in its Flint locations,” the company told me in a statement. “GM remains diligent about the safety of the water in its facilities and has worked with community organizations to support Flint residents in the aftermath of the water crisis.” The automaker didn’t respond to requests to clarify or elaborate.

At least to Williamson, the automaker shoulders more responsibility here than most people think. She retired from GM in 1991, before settling into a property she purchased along a river in a northern Michigan town. In 2002, she moved back to Flint to live closer to her son, buying a home on the city’s south side for $72,000.

When the water switch happened, Williamson said she started losing clumps of her hair. She married again in the fall 2014, but had divorced her husband within a year. Williamson said he stayed at a house in northern Michigan once the water issues emerged.

“We didn’t even make it a year because he refused to be here,” she said. Her son lives in the nearby city of Grand Blanc, but she said his wife refuses to bring their two children—both girls, ages 6 and 9—to her house. “Do you know how hard it is to accept that my grandbabies can’t come to my home?” she told me, fighting back tears.

That home she bought for $72,000? It was recently appraised last October, she said. Current value: $22,000. As a morbid memento of sorts, Williamson keeps a bag of her hair that has fallen out, along with two grossly discolored jugs of water that came from her tap.

To Williamson, the center of Flint’s water crisis isn’t a few bumbling bureaucrats; it’s the automaker whose presence in the city is ubiquitous. It may not make sense nowadays, but Flint still has signs around town that carry a nickname—Vehicle City—that’s more a monument to bygone times than a testament to today.

“All of this has been because of General Motors,” Williamson said. “What they left us with here in Flint is a broken economy, they left us with poisoned land, poisoned water and we had politicians that let them walk away here and destroy Flint.”

Vehicle City was a fitting name, once. Situated about 60 miles north of Detroit, Flint was heralded as the birthplace of GM more than 100 years ago. Today, it carries the unseemly label as one of the most violent cities in the U.S. The New York Times once referred to it as Murdertown, USA.

GM’s not what it used to be in Flint, but it’s still there. In the fall of 2015, as the extent of the water crisis emerged, the automaker announced an $877 million investment for a new body shop at its assembly plant, which employs 3,164 people and produces light-duty Chevrolet Silverado Crew and Regular Cab trucks, along with the GMC Sierra Crew. The Engine Operations plant on Bristol Road employs about 800 people who produce engines for the Chevy Cruze and Volt. GM’s Flint Metal Center produces sheet metal stampings, about 740 part numbers in all, for the Chevrolet Malibu, Volt, Equinox, as well as the Cadillac Escalade, GMC Acadia and Buick Verano.

There’s a laundry list of Flint GM facilities that closed during and after its mid-20th century expansion brought the end of numerous facilities in the city: In the 1980s, GM’s biggest manufacturing complex in the U.S.—known as Buick City—had more than 27,000 workers on site.

But by 1999, with demand shrinking for the Buick LeSabre and Pontiac Bonneville, GM closed most of the site. A powertrain facility shuttered in 2010, following the automaker’s filing for bankruptcy, with a fraction of employees shifting elsewhere. What was once the famous Fisher 1 body plant shut its doors in the 1980s.

That’s why, in part, Flint’s water woes can be attributed to the city’s infrastructure, constructed decades ago with the intention of supporting a robust industrial base—dominated by GM—and, by 1960, close to 200,000 residents.

“The management of the Water Department has constantly planned to build to anticipate the needs of a rapidly growing community,” a 1948 financing document for Flint’s water system reads. Soon after, city officials realized its water source—then, ironically, also the Flint River—didn’t have the capacity to service Flint’s needs. In the 1960s, a plan was hatched to supply the city with water from Lake Huron.

By then, GM had already started to pull out, slowly but surely. In 1978, GM employed more than 80,000 Flint-area residents, according to a study by Michigan State University. By 2015, that figure plummeted, to nearly 7,000, thanks to automation, work shifting outside the U.S. or outright closures. The days of American cars being built solely in America, and mostly by human hands, are increasingly numbered.

As industry fled, taking residents with it, Flint’s aging water infrastructure deteriorated as well. By 2015, Flint was only using about 13 million gallons (mg) of water per day, despite having an extra 90 mg of capacity to spare.

Excess capacity is known to result in high water age and lead to potential quality issues; with fewer customers, there’s less revenue to properly maintain the infrastructure, according to a report commissioned by the state of Michigan.

So when Flint switched water sources in the spring of 2014, it began sending corrosive water into a system that was ripe for creating problems with lead and legionella bacteria. (During the time Flint’s river was used by the city, 12 people died from Legionnaires’ disease and more than 90 fell ill, the cause of which is believed to be the river itself.)

“The very long water travel time from the treatment plant to many homes in Flint, would be expected to increase problems with both lead and legionella,” Marc Edwards, a Virginia Tech professor who assisted in efforts to uncover the water crisis, told me by email.

“This over-capacity was undoubtedly a major issue—losing a major customer made a bad situation even worse.”

After the carmaker was founded in the early 1900s and started to rapidly grow in the intervening years, GM had become a focal point for concerns over working conditions in the auto industry. In 1936, Flint auto workers launched one of the first automotive sit-down strikes, lasting 44 days and leading to the growth of unions across the U.S.

During the same period, the Great Migration began. Millions of black Americans relocated from the south to the northeast and Midwest. The promise of a good-paying GM job led Claire McClinton’s parents from Mississippi to Flint.

“It’s a typical story of the populace of Flint, how we got to this carriage town,” she told me over coffee at a local diner. “How it grew and become a beacon of hope for working-class people.”

One of seven children, McClinton is a Flint native who has been involved with activism over city’s water crisis since it began. The 67-year-old is a member of the team that helped test Flint water for lead and expose the problem.

“GM was the center of life for Flint,” she said. “It’s a company town, a one-horse town, and many people came up here from the South, including my parents, and many others, but particularly African-Americans. But other white workers came from everywhere to come and work in the factories for a decent job and a decent life.”

McClinton started at GM in 1972 at a Cadillac plant in Detroit. She was hired into GM’s metal fabricating plant in Flint in the early 1980s, and remained there until her retirement in 2009.

But GM’s shift away from Flint was pronounced well before McClinton’s hiring. Following World War II, the automaker pursued a corporate strategy that centered on shifting the means of production to the suburbs and away from urban cores, according to Andrew Highsmith, a University of California-Irvine assistant history professor who has extensively researched Flint.

In Flint’s suburbs, Highsmith wrote in a 2013 paper, GM constructed eight factories, all forming “an arc around the city.”

By the end of the 1950s, one-third of GM’s employees in the Flint-area had already migrated to suburban facilities. Numerous forces drove the outward move, Highsmith said:

Beyond such land shortages, a complex combination of corporate production interests and public policies drove GM’s shift toward the urban fringe. Cheap agricultural land, the growth of automobile markets outside of cities, low suburban tax rates, federal subsidies for industrial decentralization, demands by United Auto Workers (UAW) union members for large employee parking lots, readily available city services in the suburbs, and, crucially, the construction of interstate highways, all shaped Genesee County’s sprawling patterns of industrial development.

Yet without Flint, GM’s strategy in the area would’ve been futile. As Highsmith recounts, the automaker courted support from Flint officials to subsidize GM’s expansion—to the city’s own peril.

“In order to operate their facilities, plant managers required large quantities of water, sanitary sewers, and other municipal services generally unavailable in Flint’s suburbs,” Highsmith wrote. “Consequently, plant managers and other corporate officials aggressively lobbied Flint’s city commissioners to extend water and sewer lines to each of their new suburban plants.” And it worked. At least seven GM suburban facilities had water and sewer hookups, thanks to Flint, by the end of the 1950s.

The moves were not met without skepticism. Following a vote in April 1952 to provide water and sewage pipes to a new Chevy plant outside city limits, Robert Clark, the-then director of the local Congress of Industrial Organizations, slammed the city commissioners for their decision.

“In taking this action the city fathers are completing the cycle and it now appears that General Motors plants outside the city are going to enjoy all of the major services rendered by the city, including fire and police protection; water and sewage disposal—everything except the doubtful privilege of paying city taxes,” he said.

But it seemed GM’s goodwill in Flint trumped the concerns of critics.

“We have to live here,” one city commissioner said in a 1960 meeting, “and without GM Flint wouldn’t exist.” The automaker threw its weight behind a proposal to unite Flint and surrounding Genesee County under one regional government. But the fractious wedge of urban sprawl—racist housing policies, highway development, and a congressional vote in the 1950s that allowed for defense contractors like, at the time, GM, to deduct 100 percent of capital expenditures on new facilities—killed the proposal at the poll.

As the 1970s and 80s approached, GM’s plant closures in Flint ticked upward, compounding the city’s growing financial duress, forcing it to the brink of bankruptcy, according to Highsmith. To keep GM in town, city officials approved numerous tax abatements for the automaker, which “coincided with a net loss of nearly 15,000 local positions at GM,” Highsmith wrote.

The thriving company town wasn’t such any longer.

“If we have the tax bases deteriorating, we don’t have jobs to maintain the quality of life and things like this,” McClinton told me.

Flint officials have struggled to repair the Flint River’s reputation. Indeed, Edwards himself has said that the river water could’ve been rendered potable, if treated properly. But the reputation for GM was fitting, if you ask Flint’s residents.

“When they said they were going to switch to Flint River, General Motors’ name came up because we knew it had been a toxic dumping ground for a lot of the manufacturing,” McClinton said, adding: “The river itself with all of the dredge and sludge and waste from the factories was in there and we’re like, ‘Really? You going, you know, going go to go to the river?’”

Mary Dozier, a 66-year old Flint native and retired GM worker, echoed McClinton, saying she had a simple thought when the Flint River switch was announced: “Hell, no.”

“We always knew that the water was bad in the Flint River because Buick always dumped toxic waste in there,” she said. “Long time, it never was cleaned up. I guess about two years after that, they said they’d cleaned it up. They went through, dug up all the cars and dead bodies, but that was the water you never drank.”

A 1963 study from the U.S. Department of Interior said the Flint River “receives most of its pollution from two sources, industrial plants and the Flint sewage-treatment plant.” At the time, the study noted, Flint’s city commission discouraged extending its public water facilities any further for corporations in the city, noting that four Chevy plants stood out as the “largest industrial users among those outside the city.”

Despite the efforts to address pollution of the river, as well as the city’s switch by the late 1960s away from the Flint River to Detroit’s water system, problems persisted. As The Verge reported:

After the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, a 1974 study of the Flint River showed improvement upstream of the city but significant toxins downstream. Raw sewage discharges from Flint’s wastewater plant raised fecal coliform bacteria; phenol from GM plants and ammonia from the wastewater plants contributed toxic materials. These chemicals cause skin rashes, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal diseases, and other health problems when ingested.

To be sure, numerous companies and industry lined Flint’s waterways, all partly attributable for the river’s pollution. But despite the insistence of officials that Flint’s water was safe to drink after it started using the river, Dozier said she didn’t buy it. Not when there was brown water coming from her faucet.

“Brown water,” she said. “It smelled. we turned it on, and we would get brown water coming out of the faucet.” She’s been on bottled water ever since, six cases a week for cooking, drinking, whatever she needs.

Setting that scene in 2017 against the backdrop of a previous era, when families flocked to Flint, in search of a better life, the long-term impact of the water crisis feels all the more jarring.

Today, Vera Perry, a GM retiree Flint native who sits on the city’s board of education, said she feels like she lives “in a third-world country,” a far cry from the era her parents lived through when they came from Arkansas for good-paying jobs.

“When you see people lined up in those countries to go pump water, I feel just like them,” she said.

In telling its side of the story, GM has maintained that problems from Flint’s water were confined to its engine plant in the city. Last year, Automotive News published a prime example of this narrative, in a story titled “How GM saved itself from the Flint water crisis.”

“Plant officials were among the first people in Flint to detect something wrong,” the story reads, disregarding the complaints immediately pouring into City Hall upon the water switch. The story goes on:

For GM, the problem was not lead but the elevated levels of chloride in the treated river water — added to remove solids and contaminants — that began to cause “visible corrosion damage on parts coming out of the machining process,” GM spokesman Tom Wickham said last week.

[...] For months, factory officials tried to make it work. They used reverse osmosis, an advanced and pricey purification process. Additional water was trucked in to dilute chloride levels. The remediation efforts proved time consuming and costly, [GM spokesman Tom] Wickham said.

But emails between GM and the city obtained by Jalopnik portray a more concerning situation.

On May 7, two weeks after Flint started using the Flint river, Irene Bashore, an environmental engineer at GM’s Flint assembly plant sent an email to Flint water officials, raising concern about “conductivity values spikes on our intake water.”

In response, Mike Glasgow, the water quality supervisor at Flint’s water treatment plant, told Bashore that he was dealing with a broken sludge line that was integral to soften the river water. The incident hasn’t been previously reported.

“To make a long story short, we are treating roughly 20 million gallons of water a day, but only have the ability to soften about 10 million gallons a day,” Glasgow wrote.

Problems continued throughout the summer, and in August 2014, a decision was made by GM to get off the system. When the automaker finally made the push to switch off Flint’s water system, city officials were eager to answer GM’s call, just as they had a half-century ago.

The same couldn’t be said for complaints from Flint residents.

One name that sticks out in the emails is Howard Croft, Flint’s former public works director who’s now facing criminal charges for his role in the water crisis.

On August 13, he reached out to several GM officials requesting to meet and discuss its water issues.

“We will take every measure to address the current situation,” Croft wrote. A week later, GM’s Bashore reached out again to the water department with issues plaguing the assembly plant.

“GM Flint Assembly is interested in investigating the potential opportunity to be able to tie into the [Detroit water system], as also requested by GM Flint Engine operations,” Bashore wrote on Aug. 19, in a previously unreported email.

Daughtery Johnson, Flint’s then-utilities administrator who’s also facing criminal charges, responded: “We are committed to satisfying the water needs of the GM operations.”

Bashore’s maneuvering worked, and she joined officials from Flint’s engine plant in a meeting with Croft and other Flint officials at a meeting the next day.

According to meeting minutes, one discussion topic pertained to the assembly plant, which was, among other things, dealing with high chlorides in its phosphate system, “leading to streaking.”

A week after the meeting, Croft assured GM that necessary officials needed to sign off on the switch were aware of the situation and “they will be prepared to help you expedite the process.”

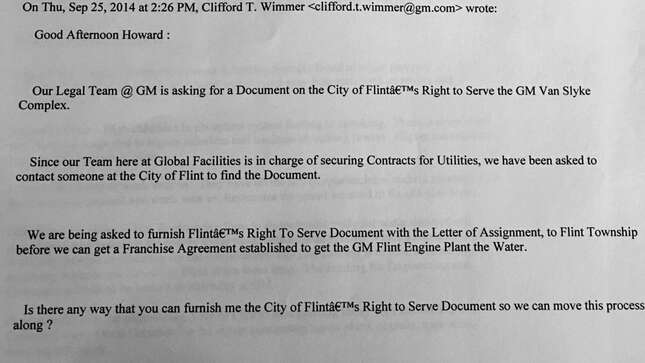

There was a snag, however. A few weeks later, a GM official reached out to Croft again, seeking a particular document that was necessary to “move this process along.”

Again, Croft was eager to help. “I will work proactively to locate the requested document and furnish it to you as quickly as possible,” he wrote in a Sept. 26, 2014, email. “I will look to include the right personnel to meet your needs.”

By mid-October, the plan was announced to the public that GM would switch its engine plant off the city’s water system, from the Flint River and back to Lake Huron water provided by the city of Detroit.

Residents, to put it plainly, were floored. Not only would the loss of GM increase the excess capacity of the system, but it’d come at a cost of $400,000 per year to Flint’s coffers.

“That was one of the single events that we knew that the powers that be don’t give a damn about us,” McClinton, the GM retiree, told me.

When juxtaposed with the response Flint residents received to their complaints about Flint’s water quality, the speed at which GM’s problems were addressed make it feel like a demarcation line in Flint’s story.

In January 2015, after dealing with three boil water advisories in the prior year, residents received an alarming notice that a high level of a disinfection byproduct called trihalomethanes (TTHM) had been found in the city’s water. Despite a growing number of complaints, officials remained adamant that Flint would stick with the river until a new regional water system was complete.

“It’s not possible to just push a button and go back,” the city’s emergency manager at the time, Jerry Ambrose, said in late January of that year, citing the additional cost. Ambrose soon after declined a formal offer from Detroit to reconnect Flint with its system.

Concerns about high lead levels emerged internally among state regulators by March 2015, but the issue wasn’t fully-known to residents at the time. But concerns over the water system continued to deteriorate. Flint’s City Council voted that month to “do all things necessary” to switch back to Detroit’s water system.

Ambrose slammed the move and used his power to overrule the vote. It boiled down to cost. How could cash-strapped Flint afford to spend the extra money for Detroit water?

Without a solid tax base, Flint was beholden to a state that could appoint a single person, like Ambrose, to run the city and implement an austere budget—whether or not residents wanted it.

A 2011 study from Michigan State University included an analysis of what Flint needed to recoup attain the level of property and income tax revenue it had the last time the city ran a budget surplus.

The study found that would require new investment equal to “almost eleven times the current assessed value of the city’s single largest taxpayer, General Motors.”

In that sense, the ability to reach those prior revenue levels was all but insurmountable.

“In the heyday, we had a lot of attorneys in the community,” Perry, the Flint education board member and GM retiree, told me. “You had a lot of doctors inside the city. You had all the big mom and pop shops. Everything was in here, and brighter. With the demise of GM, those places have gone.”

Throughout the water crisis, officials cited cost as the main deterrent for Flint’s ability to treat the river: It didn’t have money to install the equipment necessary to treat the river water before the switch was made; it couldn’t afford switching back to Detroit’s water system (only until state officials finally conceded it was necessary and kicked in some cash); it couldn’t afford upkeep of its water infrastructure, which made an already dangerous situation even worse.

“What can you happen is the biofilm [of water pipes] can harbor a wide array of what are called opportunistic pathogens,” Erik Olson, director of the National Resources Defense Council health program, told me. “These are bugs that for most healthy people aren’t going to be a problem. But if a person has been compromised that can be a big problem. One of them is legionella.”

Since October 2015, the cost of addressing the disaster for the city, the state, and the U.S. has reached extraordinary levels, with estimates exceeding more than $1 billion.

That’s what made an announcement this month from Flint’s mayor, Karen Weaver, seem almost surreal.

At a press conference on April 18, Weaver announced that she had officially recommended for Flint to permanently remain on Detroit’s water system. Residents in the audience were overjoyed—a switch to a new system was planned in the coming months, but neither they, nor officials, wanted to experience the impact of what that could do to their water quality.

“Ensuring the public’s health and safety is our number one top priority,” Weaver said.

But the dark, cruel reality was this: Weaver’s decision put Flint in the same position, on the same system it used, before the water crisis began. All that after potentially upward of $1.5 billion now needed to fix the city’s water system, of which the state and federal government has already appropriated more than $350 million to address the crisis; the potential lifelong impacts of lead poisoning in Flint’s children; and the utter obliteration of trust in government shared by Flint residents, perhaps never to be fixed again.

The revelation gave Flint’s water crisis a feel of predetermination. What was the point of it all? What possessed officials to allow this to drag on for so long?

Sitting in the room, the situation felt so far lost that you couldn’t possibly drum up an answer to the basic question of just why officials stood idly by for 18 months as a city was fed poisoned water—why there wasn’t a serious intervention from regulators, the governor, or his emergency manager until the situation had reached a fever pitch, thanks entirely to the residents and researchers who forced officials to respond.

At the very least, why was it not addressed it sooner?

A task force appointed by Snyder to review what went wrong had a firm idea of when that should’ve happened: When GM announced it was leaving the Flint system, in October 2014.

Following that decision, emails show, two members of Snyder’s executive staff said GM’s move was more than enough reason to consider switching Flint back to its previous water source.

“The suggestion made by members of the Governor’s executive staff in October 2014 to switch back to [Detroit’s system] should have resulted, at a minimum, in a full and comprehensive view of the water situation in Flint,” the task force wrote in March 2016.

Back at Weaver’s press conference, a police officer escorted a Flint resident out of the room for interrupting the proceedings too many times. The man offered one last remark, as if he was getting at the root cause of it all—just why, three years after Flint was sent barreling down this hellish path, it found itself right back where it all began.

“Middle class right here got destroyed,” he shouted. “Talk about the middle class.”