In July, an Uber driver we’ll call Dave—his name has been changed here to protect his identity—picked up a fare in a trendy neighborhood of a major U.S. metropolitan area. It was rush hour and surge pricing was in effect due to increased demand, meaning that Dave would be paid almost twice the regular fare.

Even though the trip was only five miles, it lasted for more than half an hour because his passengers scheduled a stop at Taco Bell for dinner. Dave knew sitting at the restaurant waiting for his fares to get a Doritos Cheesy Gordita Crunch or whatever would cost him money; he was earning only 21 cents a minute when the meter was running, compared to 60 cents per mile. With surge pricing in effect, it would be far more lucrative to keep moving and picking up new fares than sitting in a parking lot.

But Dave, who was granted anonymity out of fear of being deactivated by the ride-hail giant for speaking to the press, had no real choice but to wait. The passenger had requested the stop through the app, so refusing to make it would have been contentious both with the customer and with Uber. The exact number varies by city, but drivers must maintain a high rating in order to work on their platform. And there’s widespread belief among drivers that the Uber algorithm punishes drivers for cancelling trips.

Ultimately, the rider paid $65 for the half-hour trip, according to a receipt viewed by Jalopnik. But Dave made only $15 (the fares have been rounded to anonymize the transaction).

Uber kept the rest, meaning the multibillion-dollar corporation kept more than 75 percent of the fare, more than triple the average so-called “take-rate” it claims in financial reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Had he known in advance how much he would have been paid for the ride relative to what the rider paid, Dave said he never would have accepted the fare.

“This is robbery,” Dave told Jalopnik over email. “This business is out of control.”

Dave is far from alone in his frustrations. Uber and Lyft have slashed driver pay in recent years and now take a larger portion of each fare, far larger than the companies publicly report, based on data collected by Jalopnik. And the new Surge or Prime Time pricing structure widely adopted by both companies undermines a key legal argument both companies make to classify drivers as independent contractors.

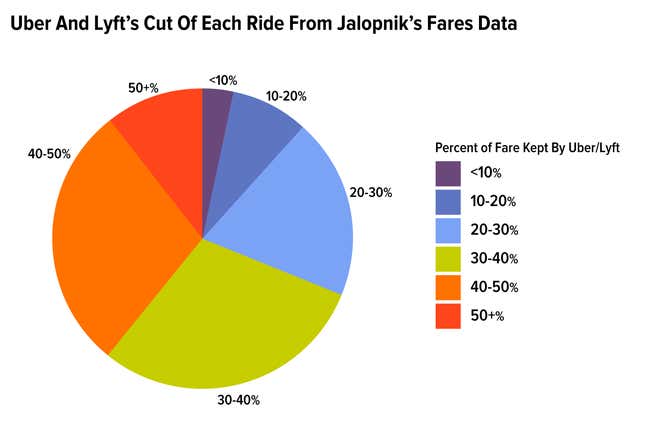

Jalopnik asked drivers to send us fare receipts showing a breakdown of how much the rider paid for the trip, how much of that fare Uber or Lyft kept, and what the driver earned.

In total, we received 14,756 fares. These came from two sources: the web form where drivers could submit fares individually, and via email where some drivers sent us all their fares from a given time period.

Of all the fares Jalopnik examined, Uber kept 35 percent of the revenue, while Lyft kept 38 percent. These numbers are roughly in line with a previous study by Lawrence Mishel at the Economic Policy Institute which concluded Uber’s take rate to be roughly one-third, or 33 percent.

Of the drivers who emailed us breakdowns for all of their fares in a given time period—ranging from a few months to more than a year—Uber kept, on average, 29.6 percent. Lyft pocketed 34.5 percent.

Those take rates are 10.6 percent and 8.5 percent higher than Uber and Lyft’s publicly reported figures, respectively.

In regulatory filings, Uber has reported its so-called “take-rate” is actually going down, from 21.7 percent in 2018 to 19 percent in the second quarter of 2019 (Uber declined to offer U.S.-only figures for a more direct comparison to Jalopnik’s findings).

Business Insider has previously reported Lyft’s take rate for 2018 was 26.8 percent, although Lyft claimed it does not publicly share their take rates and declined to do so with Jalopnik.

When asked for comment, Uber and Lyft disputed Jalopnik’s findings as flawed and not representative of their overall business. But neither company agreed to Jalopnik’s request to provide statistically significant data sets of anonymized fares for independent verification, continuing their longstanding pattern of data secrecy.

Trips like the $65 Taco Bell run only highlight inequities between the multibillion dollar companies and drivers earning at or below minimum wage. When asked about that fare, an Uber spokesman acknowledged, “For all the pain points new surge helped solve, it has its challenges: top among them is the fact that drivers may earn comparatively less on longer surged trips, even if they earn surge more frequently.”

The spokesman added that “To better serve drivers, we often increase surge payments on longer trips with added amounts that vary based on the length of a trip. Drivers are able to see this additional amount on their trip receipt after the trip is over.” Dave received no such increase.

Trips like Dave’s also expose inconsistencies in the very logic under which these companies operate. Drivers like Dave are technically independent contractors, but they have no control over many aspects of their work life, including the price of their own services.

“This is really fascinating and troubling,” said Sandeep Vaheesan, legal director of the Open Markets Institute, a nonprofit studying corporate concentration and monopoly power, when briefed on Jalopnik’s findings. Vaheesan went on to say the findings “support the argument that their business model is built on large scale labor exploitation.”

“This is, as far as I know, the most convincing data that we have at the individual driver level about the share that Uber takes of every driver’s gross earnings,” said Marshall Steinbaum, an economist at the University of Utah who studies labor markets, “and in that respect it moves the ball a lot forward in terms of understanding how these labor markets work.”

He added that “if their [Uber and Lyft’s] response is this is not representative of all the drivers, it is representative of other people who have tried to verify their claims and found them wanting.”

To be sure, Jalopnik’s data set is not perfect. The sample of 14,756 fares is a tiny fraction of the millions of trips Uber and Lyft complete each day in the U.S. alone; it would be impossible for any independent researcher to get their hands on an adequate data set without Uber and Lyft’s cooperation (or, in theory, more nefarious methods such as hacking or data breaches).

And there is almost certainly some degree of selection bias in Jalopnik’s data acquired via the web form toward drivers who are unhappy with their share and would therefore be more likely to take the time to submit their fare. Along those lines, the fares Jalopnik received through the web form were disproportionately from outside of Uber and Lyft’s major metropolitan markets and during surge times, indicating a possible selection bias in our findings.

“While 8,926 fares is a large increase from the 175 you had before,” an Uber spokesman said, “it is still not a statistically representative sample, given Uber completes approximately 15 million trips per day around the world.”

But there are also reasons to believe our findings are more representative of the individual driver experience than Uber and Lyft would care to admit. Even the complete fare records Jalopnik received showed a higher take rate than previously reported. And these drivers, Steinbaum observed, may present a selection bias in the other direction.

By keeping diligent records, “they’re probably the savviest drivers and therefore the ones that the companies are least able to fleece, so to speak, so you might be getting an underestimate of their take from them.”

Lyft disputed this as well. A spokesman told Jalopnik, “Even if the investigation looked at every ride for a handful of drivers, the sample pool of drivers needs to accurately reflected [sic] a cross section of all Lyft drivers, and not just a specific subset (i.e., did that sample size have enough diversity to say it represents the average experience for Lyft drivers across the board).”

In regulatory filings, court cases, and their terms of service, Uber and Lyft claim to merely be facilitators between the rider and driver, not a transportation service. They claim their actual customers are drivers. And drivers pay Uber and Lyft a cut of their earnings for connecting them with their customers, the riders. This echoes a common Silicon Valley refrain: they are just technology companies, and therefore should not be subject to the regulations of the industries they are disrupting.

But in recent years, in efforts to stem the tide of their multi-billion dollar losses, both ride-hail companies have separated what riders pay from what drivers earn, moving away from a strict percentage-based commission.

Using what it calls Upfront Pricing, first instituted in 2016, Uber tells riders exactly how much they will pay before the trip begins based on their own algorithm’s prediction (as is often the case, Lyft instituted the same policy shortly after Uber). It then compensates drivers based on the trip’s actual time and distance.

According to both companies, the change to Upfront Pricing was made in response to rider and driver feedback; riders didn’t want to be surprised with a higher bill, and drivers wanted to be compensated for the work they actually performed.

This common-sense policy has potentially profound legal implications. In practice, Upfront Pricing decouples the rider’s payment from the driver’s earnings; one price is set before the ride based on an estimate, the other after the ride is completed based on reality.

This change is most evident with how Uber and Lyft now handle high-demand periods. Along with the move to Upfront Pricing, both companies also changed the way their high-demand pricing model, often known as Surge or Prime Time works (Lyft has since changed the brand name to Personal Power Zones for drivers).

Instead of drivers receiving a multiplier on their earnings, as Dave did for the Taco Bell run, most now get a flat fee bonus, typically only a few dollars per ride. Uber and Lyft will sometimes kick the drivers a couple extra bucks if the surge is particularly high or the ride especially long, but there seems to be little rhyme or reason for when this happens. Riders, meanwhile, still pay the multiplier, meaning riders are often paying far more than drivers are earning on those rides.

An Uber spokesman explained this dynamic to Jalopnik as follows: “While driver- and rider-side surge are both tied to real-time imbalances in supply and demand, what a rider pays in surge and what a driver earns from surge on a given trip isn’t always the same. This is due, in part, to the fact that new driver surge is based on the driver’s location, not the rider’s. What this means is that a driver may receive surge on a trip even if the rider doesn’t pay anything extra.”

Similarly, a Lyft spokesman said, “Lyft continues to pass the rider Prime Time onto the drivers, via PPZs, at the same rate in aggregate. There are differences on a ride-level but these differences cut in both directions,” in that sometimes drivers earn an usually higher or lower percentage of the fare.

In other words, Uber and Lyft say they are taking all the surge charges riders pay and spreading the proceeds among all the drivers in the area, whether their particular passenger pays a surge fare or not (both companies deny they merely pocket the difference).

This, according to Wayne State University law professor Sanjuka Paul, who has written extensively on the ride-hailing industry, is a new wrinkle in the independent contractor debate, because it doesn’t align with the arguments the companies make that they merely facilitate interactions between two independent actors in a market.

“The economic reality is they, Uber and Lyft, are collecting the fare from the consumer and then making a capital firm decision which, in this case, doesn’t sound like a very bad decision— actually making quite a sensible decision,” she said. “But it shows that they are a firm that is charging consumers and then making decisions with that money, including how to pay a labor force.”

Or, as Steinbaum put it, “what they’re doing is exactly what employers do with their workers.”

In addition, the companies can, and have, changed the base time-and-distance rates drivers earn whenever they want. And there have been many pay cuts.

In recent years, driver forums have been flooded with angry comments about hastily announced pay cuts in markets around the country. This, despite drivers already making near (or sometimes below) minimum wage. These cuts have led to some drivers who spoke with Jalopnik on the condition of anonymity curtailing their own hours, or exiting the ride-hail business entirely, because it’s no longer worth their time after accounting for expenses like fuel, insurance, and car payments.

Uber and Lyft both deny that driver earnings have declined. “While not every driver has the same experience,” an Uber spokesman wrote to Jalopnik, “that’s not what we see when we look at trends in drivers’ average hourly earnings over the last couple of years, which have increased.”

A Lyft spokesman told Jalopnik the number of drivers on their platform is increasing and that driver earnings increased over the past two years. The company claims drivers make “more than $30 per booked hour nationally,” although that figure only accounts for the time from when a driver accepts a ride request to when the passenger is dropped off and does not include expenses.

Some drivers didn’t even realize the extent of the changes in the company’s take rates, both for high-demand trips specifically and across the board, until they compiled their records to send to Jalopnik. One driver, who has been working for Uber in Texas for three years, sent us almost 500 surge fares.

“Kind of depressing to know that Uber used to take 20 percent when I started and now gets on average 31 percent, with some fares up to 50 percent,” he said.

A former full-time driver from Iowa said that prior to the pay cuts that ultimately slashed his per-mile rate more than half, he estimates about 30 percent of the fares he picked up were, after Uber and Lyft’s cut, not worth his time. After those changes, from 2018 onward, he says the number of undesirable fares is now closer to 70 or 80 percent, which is why he stopped driving full-time.

(It’s tricky to compare ride-hail take rates with the taxi industry in any meaningful way, where drivers are on the hook for fixed expenses such as dispatching services, leasing the taxi and/or paying off the cost of a medallion. Taxi drivers have to pay those fees regardless of how much money they earn. In fact, many taxi drivers switched to ride-hailing because percentage-based commissions—along with the hefty sign-up bonuses Uber and Lyft once offered—sounded like a better deal.)

The drivers’ frustrations with pay cuts and Uber and Lyft’s rising take rates are compounded by other inequities of the ride-hail industry.

Uber and Lyft argue that drivers are not employees, but independent contractors, since they are allowed to set their own schedules. Both companies lean heavily on this arrangement in advertisements and promotions to recruit drivers, using phrases like “be your own boss” to describe the arrangement.

But the reality is much more complicated. In fact, drivers don’t have the power to make many of the decisions that typically come with self-employment. Chief among them is the ability to set prices—or even negotiate—for the services they provide.

In driver agreements, both companies state that drivers accept their new rates simply by continuing to drive for the company. In other words, the only recourse drivers have to a pay cut is to quit; a familiar arrangement for any employee, but not for anyone who is their “own boss,” and thus would not have income determined by another company’s ever-changing set of rules.

“It’s really crazy how companies have carte blanche to deprive us of our rights through contract,” Vaheesan wrote in a follow-up email after Jalopnik showed him the contract language. “Courts and Congress have basically accepted this regime as normal.”

Furthermore, drivers have the option to decline or cancel rides, but there is widespread belief among drivers that if they do it too often, they risk being put in “timeouts” where they receive no requests at all for a certain amount of time, a phenomenon that is frequently documented in driver forums and blogs.

Both companies deny they punish drivers in any way for declining rides, but Lyft acknowledged some incentives are only available to drivers with high ride acceptance rates.

In another bid to increase revenue, Uber is rolling out Comfort Mode, which provides riders amenities such as a car with extra legroom, the option to set a desired temperature, or request the driver to be quiet for an extra fee (drivers for Comfort rides get a few cents extra added to their mile-and-time rates).

Uber says this is merely a request to the driver rather than a requirement, but riders are unlikely to be pleased if a driver refuses to comply with a request they paid extra for. Should a driver not follow the instructions, it is likely they would at the very least receive a lower rating.

Taken together, rather than being their own bosses, drivers often feel as if they are being governed by algorithms, as Alex Rosenblat wrote in her deeply reported book Uberland: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Rules of Work. This algorithmic “boss,” which sets pay rates in opaque ways and governs work rules through carrot-and-stick arrangements, not only removes any accountability but results in drivers having to guess what the algorithm wants. In her book, Rosenblat wrote:

An algorithmic manager enacts its policies, penalizes drivers for behaving in a manner unlike what Uber “suggests,” and incentivizes them to work at particular places in particular times…When I ask drivers if they are their own boss, they usually pause and remark that it’s sort of true, and that they set their own schedule. But an app-employer provides a type of experience that differs from human interactions, and it can be challenging to identify the fault lines of autonomy and control within its automated system.

In an interview for this story, Rosenblat, who spoke to hundreds of drivers researching her book, added that drivers had different reactions to rides where they thought they didn’t get a fair cut.

“Some drivers were pissed, and they would say, if I’m an independent contractor you should give me the information I need to make an informed choice,” Rosenblat said. “But other drivers rationalize taking bad fares with the idea that taking a bad one is kind of like karma… If you only take a passenger a couple of blocks on this ride, you might get compensated for a better ride later.”

Rosenblat added that the karmic realignment theory is a direct result of the lack of transparency from the ride-hail giants. She characterized it as a “magical thinking [drivers] wouldn’t have to resort to if Uber and Lyft gave them the actual facilities to make informed decisions, or to better understand how they might be treated, or rewarded and penalized, for their work performance with valuable or less valuable dispatches.”

A full-time veteran driver from New Orleans told Jalopnik that she somewhat subscribes to the karmic realignment theory on the take rates, although recent cuts have changed her attitude a bit. She has seen her earnings drop roughly 20 percent this year due to a combination of factors, including an expanding of the driver pool as a result of the companies allowing older vehicles than prior years. As a result, she is considering a job change, even though an occasional health issue makes the flexible hours of ride-hailing especially appealing.

Even though she prefers driving to her previous jobs in the service industry, she said she has come to believe Uber and Lyft’s take rates ought to be capped, perhaps at 25 or 30 percent, and said she would get behind a driver organizing campaign to make the profession more sustainable.

But for now, she still avoids looking at individual fare breakdowns. “It just annoys me,” she said, “and there’s nothing I can do about it.”