The Nissan Frontier gets a lot of hate. The current version’s been in production for 15 years and the design, powertrain, and interior quality are now thoroughly outdated. To see if the old truck has any redeeming qualities, I took two through muddy forests trails in central Michigan. It was a shitshow resulting in damaged vehicles, but I came away convinced the Nissan Frontier deserves more respect.

Helping me with this test were my friends Chris and Derek, the two Ohio State grads and former Nissan engineers who enabled my purchase of my dream Jeep Cherokee last year. Plus, there was Adam, the Ford engineer who helped me gut my Jeep J10's manual transmission, and there was Adam #2, a Nissan engineer and friend of Chris and Derek’s.

Adam and Chris—who own a 2015 Nissan Frontier PRO-4X and a 2016 Nissan Frontier SV 4x4, respectively—were keen to take their machines off-road for the first time. The former was especially keen, as he has been eying the Jeep Gladiator, but wanted to make sure he enjoyed wheeling before dropping the cash on such an off-road focused machine.

So two weeks ago, the five of us drove from metro Detroit roughly three hours north to meet at an Air BnB near Harrison, Michigan’s Rocks and Valley’s Off-Road Park.

Adam bought his Pro-4X a few years back while searching for something with a manual transmission, plenty of room to haul big items to the house that he’d recently bought, and a tendency to actually function when he needed it (his BMW had crapped out in the dead of winter). Chris had bought his black SV, like Adam, for its utility.

Towing With The Nissan Frontier

Adam and Derek left in the Pro 4X , while Chris and I met at my friend’s house to snag a trailer to tow my Willys CJ-2A. The plan was for me, an experienced off-road enthusiast, to use the 1948 Jeep to lead Chris and Adam on their first-ever off-road journey.

After struggling to start the Willys in the cold, I froze my ass off driving it over half an hour in 40-degree weather, and met Chris at my friend’s house, where we prepared the trailer and strapped down the Willys.

To hook up the trailer, Chris slowly backed his black Frontier up while I shouted instructions since Chris had rendered his backup camera useless by replacing the Frontier’s crappy stock infotainment screen with an aftermarket one. As we worked to get the hitch ball aligned properly using flashlights to augment the reverse lights, I was surprised to notice a nice growl from the Frontier’s exhaust.

The Nissan Frontier, as I would later confirm while my friend hammered the throttle off-road, is the best-sounding mid-size truck on the market, period. I can’t say I was expecting that, since I think naturally aspirated V6s generally sound boring. Nissan’s VQ-family of engines, though, is known to be among the better sounding V6s, so perhaps I shouldn’t have been too surprised by the truck’s awesome low-frequency rumble.

Unfortunately, while the exhaust note was nice on the outside, on the inside, the Frontier’s engine sound was an annoyance. I drove Chris’ Frontier SV 4x4 on the highway heading north from Detroit, and while there was remarkably little wind noise in the cabin aside from a tiny bit coming from near the A-pillars, and there was only a moderate amount of road noise, there was quite a bit of drone from the 4.0-liter VQ40 V6 engine.

Even at the low 2,100 RPM that the truck held while towing the roughly 6,000-pound load at 70 MPH on the flat highway, there was a prominent low-frequency noise emanating from ahead of the firewall and quieting markedly when I let off the pedal.

The good news is that the noisy motor feels powerful. At 261 horsepower and 281 lb-ft of torque, the 4.0-liter V6’s output is competitive with the rest of the mid-size truck class. Sure, that engine is mated to a lazy five-speed automatic whereas most modern vehicles have eight or more gears in their transmissions, meaning the Nissan holds gears quite a bit longer than other trucks. But for the most part, I was satisfied with the powertrain.

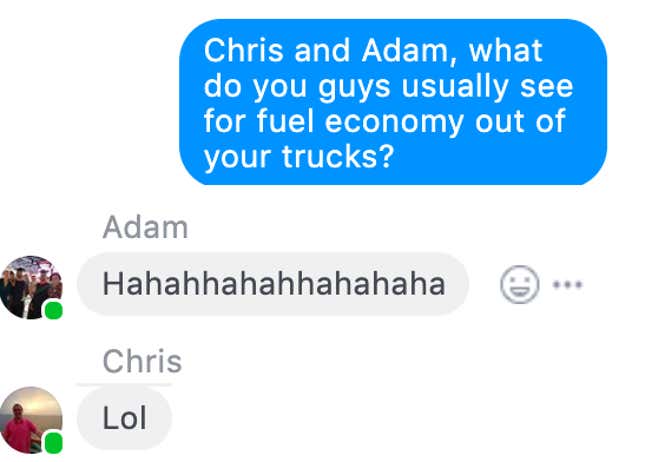

The downside to the old motor and transmission, the ancient architecture that makes the truck as heavy as significantly larger competitors, and sheet metal that could probably be a bit more slippery, is that fuel economy is awful. It’s probably the number one complaint I’ve heard from Chris and Adam about their rigs. In fact, when I asked the two what kind of fuel economy they averaged, here’s how they responded:

The Automatic 4x4 is EPA-rated at only 15 city, 21 highway, while the manual gets 16 city, 21 highway. These fuel economy figures have remained the same since the 2013 model year. With a mix of highway towing and around-town driving, we managed about 13 mpg in Chris’ automatic SV. Unladen, Adam and Chris say they tend to average “maybe 15 or 16” and “around 17,” respectively.

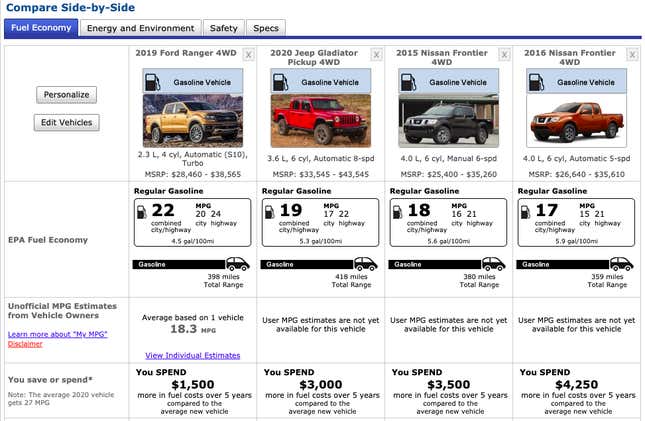

Those are pathetic figures. The Ford Ranger and even the heavyweight Jeep Gladiator offer significantly better fuel economy, as shown below:

What I noticed while towing the Willys is that the Frontier’s front end felt a bit light, and the truck wandered a bit, requiring steering input to remain straight. The trailer fastened to the truck’s rear hitch felt and sounded like it was jumping around a bit over bumps. Both of these issues, I bet, had more to do with our trailer setup—tongue weight and play in the hitch—than with the Frontier’s limitations. Otherwise, the truck towed right up against its ~6,300-pound limit gracefully and comfortably.

During our towing excursion towards the off-road park, Derek called us with disappointing news: The park’s website indicated that the spot would be closed during the entire month of November. In other words, we’d spent weeks planning a trip to a place that wasn’t even open. We were idiots.

After assuring everyone that we’d figure out a way to have fun off-road, Chris and I arrived at our AirBnb in a quiet neighborhood off the shores of Michigan’s Houghton Lake, where it was clear that winter had already begun.

As the sky dumped snow, the five of us automotive engineers holed up in a small cabin in rural Michigan talked about cars for hours and hours until sheer eyelid fatigue finally shut us up.

Off-Roading The Frontiers

The following morning, we woke up ready to off-road, but shortly after shoving the Willys off the trailer, we realized that the little farm Jeep wanted to keep sleeping. Try as I might, the thing wouldn’t start, and I found that the little half-hour drive I’d done the previous cold night had not just consumed oil, but contaminated what was left in the crankcase with coolant (there appears to be too much for it to have been just condensation, I think):

Out of an abundance of caution, I changed the Jeep’s oil, and then the two Adams, Chris, Derek and I began troubleshooting the no-start problem. There’s a lot of engineering know-how between the four people in this picture:

Still, despite our technical knowledge (and remember, Engineers Are Not Mechanics) our time was limited, and we wanted to get a full day on the trails. So, after about an hour, we gave up on the Willys and left it at the AirBnb, resolving to fix the machine later that night. We had some off-roading to do, so we hopped into the Frontiers and went on our way.

As we’d initially planned to drive at Rocks and Valleys off-road park, but because of the whole “closed” situation, we had to improvise a bit. So we snagged some off-road vehicle licenses and headed out into the woods in search of trails.

And my god did we find them.

The forest trails were totally waterlogged—mudfests, I’d go so far to say. Our first obstacle was a dirt mound in an open “play area” in the woods. It wasn’t anything wild, but it got Chris and Adam into low-range, and it tested not just the traction from their tires, but also approach, departure, and breakover angles.

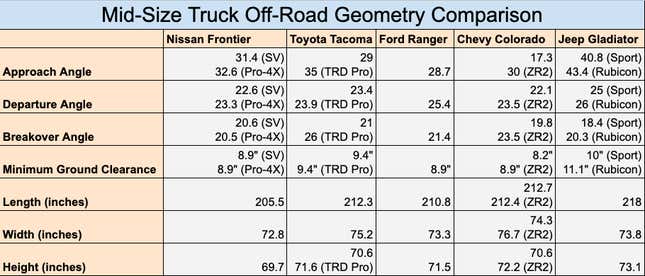

Speaking of those figures, the Nissan Frontier PRO-4X like Adam’s has a 32.6-degree approach angle, 23.3-degree departure angle, and 20.5-degree breakover angle, while the Chris’ “SV” trim’s approach angle is a bit lower at 31.4 degrees, departure angle is also down a bit at 22.6 degrees, and breakover angle is up a negligible amount at 20.6 degrees. Ground clearance is exactly the same on both trims at around nine inches.

So, geometry-wise, the two trucks are quite similar, and both are actually decent for the segment. Their approach angles are quite good, below only the Jeep Gladiator and Toyota Tacoma TRD Pro. The departure angles leave some to be desired, but they’re not that far off of the Tacoma’s and not as bad as the non-ZR2 Chevy Colorado’s.

The roughly 20.5 degree breakover angle also isn’t great, but it’s not that much below the standard Taco’s, it’s higher than the standard crew cab Colorado’s (whose data above is based on the 2016 model’s press release—the vehicle hasn’t changed much since), and it’s significantly better than the Gladiator’s. Ground clearance is right in line with the rest of the pack, though lower than the Gladiator’s.

Perhaps equally as important, and one of the things that I absolutely love about the Nissan Frontier, is that it’s actually the right size. Mid-size trucks, as I’ve written before, have become bloated, but the Nissan Frontier remains old-school in that respect, coming in at six inches shorter than the next smallest body-on-frame mid-size truck shown in the table above. It’s also narrower than the competition and not as tall. Despite this, the Frontier still weighs quite a bit at somewhere between 4,300 and 4,600 pounds—fairly in-line with the much larger competitive trucks.

Aside from decent geometry, both the SV and PRO-4X Frontiers have a 2.625:1 low-range transfer case, a solid rear axle that offers decent articulation, and a brake-based limited-slip system, though the PRO-4X adds Bilstein shocks, skid plates (fuel tank, transfer case, oil pan), an electronic rear locker, and more aggressive all-terrain tires.

Once we got tired of testing the Frontiers’ geometry at the wide-open play area, the five of us in the two trucks continued down some random dirt trails, eventually reaching the first of many enormous puddles we’d encounter during our trip. After a quick depth-check with a stick, Chris and Adam hammered their throttles and splashed through the puddle. There was great joy.

The rest of the day involved driving down tight, muddy, and snowy forest trails. We got to use Adam’s Frontier’s front recovery hook to yank a fallen tree out of the way:

That led us down a ridiculously tight, snow-covered trail that required me to step out every two minutes to push some sticks out of the trail so the trucks’ paint wouldn’t get scratched.

Eventually, the trail became steep, and Adam’s nearly-bald tires began showing their weakness, as the white pickup struggled to crest the hill:

Shortly after the video above, Adam actually backs his truck into a tree, marking the beginning of what would be a string of unfortunate events resulting in multiple damaged vehicles.

Chris’ black Frontier SV made it up the grade without issue, thanks largely to the better tires and possibly the easier wheel speed control thanks to the automatic transmission. Unfortunately, the grade led us to a dead-end, so we turned around, drove back down the narrow snowy trail, and then continued down some less snowy, more muddy paths.

There were so many puddles, we stopped getting out to check their depths, for it would have taken us hours to go just a single mile. This decision would come back to haunt Adam and his white PRO-4X just a few moments later, and then it would haunt my Willys and me the following day.

For hours, the five of us in those two Nissan Frontiers drove through mud pit after mud pit in the middle of the woods, rather aimlessly. Everyone was having an excellent time, and both trucks were doing great.

Despite the off-road add-ons, I’d say Adam’s PRO-4X actually performed a bit worse than Chris’ SV. Admittedly, Adam’s truck’s rear locker was giving him trouble, and his tires were pretty close to bald, and I was impressed by Chris’ cheaper SV. It offers similar off-road geometry (approach and departure angles, rather small overall size) as the more expensive PRO-4X, but at a lower cost. Other mid-size trucks in this segment require you to buy the most off-road oriented variant, or else make major sacrifices to capability.

The day came to an end when Adam, who had already backed into a tree earlier in the day and dented his bumper, got really, really stuck.

Breaking The Nissan Frontier PRO-4X

As the guide to this whole off-road excursion, this was my fault. I should have made sure he drove his truck closer towards the edge of the puddle, as I was instructing in the video above.

Unfortunately, in part due to his dysfunctional rear locker and bald-ish tires, and especially due to the lack of ground clearance under the front suspension, Adam’s white PRO-4X was beached in some thick muck.

I jumped into the cold water to dig some of the mud out from the truck’s front suspension cradle, but the floor of the puddle was so soft and soupy, it was futile. We had to go for the tow.

I hooked a strap to the PRO-4X’s hitch, and then to the SV’s front tow hook. Chris backed up until the rope was taut, and then gradually pressed the rightmost pedal to the floor. Adam, with his truck in reverse, let off the clutch and gave a bit of gas, and the two VQ-series motors sang a glorious tune that pervaded the forest. But neither vehicle moved.

Chris crept forward, then got a bit of a running start. The rope quickly lost all of its slack, the black Nissan’s nose dipped as the tow-hook at the base of its fascia bore the tension of the yellow strap. Still, there was no progress.

Eventually, we turned Chris’ truck around, and when Chris still wasn’t able to get the PRO-4X out by pulling with his hitch, I offered to take over. My first tug felt as if I were yanking against an immovable wall; The strap we were using wasn’t a snatch strap, but just a nylon tow strap with little stretch, so when the slack went away, the truck I was piloting stopped abruptly and violently.

Having spent much of my adult life getting vehicles out of mud pits, I knew I’d eventually get this white truck out of the hole, but I didn’t anticipate how much of a beating it would take.

The first bit of damage was entirely my fault because I forgot to do something that I always do when trying to tow a vehicle: I forgot to put a floor mat over the tow strap. In this case, the strap actually consisted of a real nylon tow strap tied to a tie-down strap that had fallen off a big-rig, but that I’d repurposed to be a recovery strap.

The problem is that the nylon tie-down didn’t have loops at its ends, so I simply tied loops myself. This, it became apparent when the strap broke at the knot when I gunned the black truck from a stop, had created weaknesses in the rope. The now-broken, heavy (because it was saturated with water) knot at the end of the rope—with no floor mat over it to weigh it down—shot violently towards the white truck and BANG. It hit the tailgate, leaving a dent. It’s a bit hard to see the damage, but it’s a roughly-golfball-sized dent:

This could have given someone a nasty bruise, and it reminded me never to skip the “weigh the tow strap down with a floor mat” step of the recovery process.

With the tie-down-strap half of the tow rope broken, we backed the black Frontier closer to the PRO-4X and made do with simply the single strap. After a few violent tugs, the white truck emerged from the muck, revealing further damage:

The bottom of the front fascia had come off, and so had a ridiculously-thin front skid plate that I thought was made of plastic, but was apparently sheet metal.

By the time we got the truck out of the pit, it was dark and cold, so we headed back to the AirBnb. First, Adam and I drove to O’Reilly Auto Parts to see if we could fix his front fascia and skid plate, the latter of which is shown below:

It was quite miserable outside, but Adam and I found the fasteners in the store, and were able to get the skid plate and lower fascia into decent enough shape. The following-morning, Adam zip-tied the fascia to the point where, unless you were looking for it, you probably wouldn’t have noticed any damage.

That night, I replaced my Willys’ condenser, re-adjusted the points, and actually got the machine running.

Breaking My 1948 Willys CJ-2A On The Trails

Of course, by the time the morning came around, it was hard to start, and I eventually ran out of battery. The solution was what has to be the most idiotic starting procedure ever recorded in human history:

We hooked the tow strap from Adam’s Frontier to the Willys, and used the driveway as a sort of “runway.” We had about 100 yards to bump start the Willys. I put the transmission into reverse, pushed my left foot against the clutch pedal, and waited until Adam was pulling me a few miles an hour, before quickly letting off the pedal, and hoping the rear tires would have enough traction to spin up the engine.

The tires skidded quite a bit, but they were able to turn the engine over. The problem was that the engine wouldn’t idle. I had to keep the revs up or it’d shut off, so to start the Jeep and keep it running, I had to let off the clutch with my left foot, let the engine start, use my right foot to give the engine gas, use the left foot to quickly hit the clutch again so I could shift out of reverse and into neutral, then quickly shift my left foot to the brake pedal so I didn’t ram into Adam.

It was quite a process.

In time, we got the Willys warmed up to the point where it’d idle just fine even with my foot off the gas. Then we hit the trails, and for some reason, after I ripped some donuts (see below), the engine refused to idle again.

I bumped the idle up a bit with a screwdriver, but even after that, I ended up driving through the trails with my foot feathering the gas at all times. This wasn’t too hard to do since the Jeep had such low gearing, but sometimes I had to stop, and I ended up stalling the motor a number of times. My friend Derek, wearing the black and gray sweater in the photo below, had a 12-volt battery and jumper cables on quick-draw so that he could quickly get the Willys back up and running anytime the engine shut down. That poor bastard, Derek.

The rest of the day was a lot like the prior day, except I was leading the pack in the Willys, and I can tell you this: I didn’t give a damn about anything. I mean, truly, I absolutely sent it. I was planning to begrudgingly sell the Willys the following week in an effort to rid my life of the burden that is owning more than 10 cars. So I figured one last hardcore hurrah for old times sake seemed appropriate.

I aimed the nose of that Willys straight through the heart of every mud pit on the trail. The 5.38:1 axle ratio, along with the 2.46:1 low range ratio and the 2.79:1 first gear, yielded a ~37:1 crawl ratio that was plenty for the tiny Jeep with its torquey 134 cubic-inch “Go Devil” motor. The wheels just kept turning no matter how big of a rock I hit or how thick of mud I plowed through; There was torque for days.

It was glorious. I drove with my windshield down, and listened to the classic high-pitched sound of that World War II-derived engine rumble through the woods as the 31-inch all-terrain tires grappled with and ultimately overcame everything in their path. It was pure bliss, and it was hard not to fall in love with the unstoppable little 4x4 all over again.

Then my hubris caught up with me:

I aimed the Jeep for the center of a rather large mud pit, and after getting about six feet into it, the water level rose to an alarming level as the tires completely immersed themselves in filth.

I kept my foot on the gas, praying the deep pit I was in would get a bit shallower, but the Willys’ forward progress ceased. I popped the three-speed transmission into reverse to try to back out, but then the motor died.

I rolled up my sleeve and reached into the cold water with the tow strap that someone had thrown me. Eventually I found the hitch at the rear of the Jeep, hooked the strap up, and held on for dear life as Chris pulled me out with his Frontier.

He tugged the Willys all the way back to a sloped road just near where we’d parked the car-hauler. Chris hooked up the trailer, placed it at the bottom of the slope, and then we participated in a high-risk, low-intelligence trailer-loading scheme relying far too heavily on gravity.

We estimated the track width of the Willys using the tow rope, and then set the trailer’s ramps that far apart, before my friends pushed the Willys down the slope with me behind the wheel, barreling toward the back of the trailer, praying to the Jeep gods that we hadn’t mis-measured the track width.

Luckily, we made it right up the trailer without issue.

Adam #2 hopped into a Nissan 370Z convertible that he had strangely driven to the trail with its heat on blast but roof down and left, while Derek, Chris, and I began our long drive down interstate 75 back to the Detroit area.

We arrived at my house rather late, rolled the Willys off the trailer onto a nearby road, and pushed the Jeep a few hundred yards down a sidewalk to my front yard, where it sits today.

Then I drove another one of my Jeeps to help Derek and Chris dump the trailer off at my friend’s house about an hour away, and we all went home. A few days later, I went to check my Willys oil, and realized that all the water that had entered the crankcase had turned into a block of ice, and I was unable to remove the dipstick.

A few weeks later, the weather got warmer, and here’s what I found when I went to change my oil:

Yes, I surprise myself with my own stupidity sometimes.

Verdict On The Nissan Frontier

The Nissan Frontier is old. Its interior is filled with lots of hard plastics with absolutely no indication that design aesthetics was even a consideration. The manual transmission’s shifter is strangely rubbery and unsatisfying and the automatic doesn’t have enough gears, the ride is pretty harsh over washboard dirt trails, the truck is heavy, it sucks fuel like crazy, its engine drones on the highway, and per Adam, it’s hardly the most reliable of machines.

But it sounds pretty damn good, it feels reasonably powerful, it’s the right size for a mid-size truck, you don’t have to get the top-spec model to have genuinely decent off-road capability, and above all, you can have a hell of a lot of fun in one.

The Frontier is priced about the same as a Ford Ranger; You can get a 4x4 crew cab for under $32,000. If you’re choosing between the two and they’re about the same price, then you’re going to want the Ranger (The Ford is just more modern; it literally has double as many gears as the Nissan).

But if you can find a Frontier for cheap, and you’re looking for a small-ish truck that can handle itself off-road, I say go ahead and pull the trigger. I bet you’ll like the ancient little workhorse.