Helen Hudson will tell you what the 15th Ward was like when she was a girl. In the 1950s and early ’60s, the Syracuse neighborhood was home to thousands of predominantly black residents who had settled in the growing upstate New York city during and after the Great Migration. Those who remember it, like Hudson, describe it as thriving, self-sufficient community they were proud to call home.

“Oh my god, the things we had,” she said recently, her voice softening with the distinct twang of nostalgia. “We had two bowling alleys. We had meat markets.”

Charlie Pierce-El will tell you all about it, too. His eyes will light up when he does. Mr. Betsy’s was the first grocery store in the neighborhood. Restaurants lined Harrison Street, many of them serving soul food. Pierce-El refused to pick a favorite, because “they were all favorites, back then, being a young man.”

He frequented the five theaters available within a short walking distance, once to see James Brown. He spoke lovingly of his mother’s garden and the resources she pooled with neighbors to create fresh meals for his father, an auto detailer, and his 11 siblings.

Hudson, Pierce-El, or any other former residents of the 15th Ward won’t lie and say it was a rich neighborhood. But it was the type of working class community where blocks were extensions of families and lack of material wealth was compensated by a sense of belonging.

Yet, to others—to the newspaper writers and the city planners and the real estate developers who had no desire to sell homes to black people—the 15th Ward was a slum, filled with cockroaches and blight. To them, it didn’t need to be fixed. It needed to be knocked down.

Then the calls for “urban renewal” came. And not long after that, the highway came too.

Today, Syracuse is a city reckoning with the sins of its past. Sins that built a highway right through and over the 15th Ward to enable quick travel out to the suburbs, and consequently enabled white flight away from the city that destroyed the city’s tax base. The highway, part of Interstate 81 which now runs from Tennessee to Canada, contains a 1.4-mile elevated section called a viaduct right along the former 15th Ward and the current Syracuse neighborhood, the South Side, which is still predominantly African-American and has a median household income just under $23,000.

But the viaduct—which was completed in the early 1960s along with a junction to I-690 right at the heart of Syracuse, combining for over one million square feet of deck space—is at the end of its useful life, like many urban highways across the country from that time. It will soon cost too much to maintain. Something needs to be done.

The potential solutions to that problem are part of a bitter fight that has divided this city largely among racial and geographic lines. One option is to rebuild the viaduct right where it stands, only bigger.

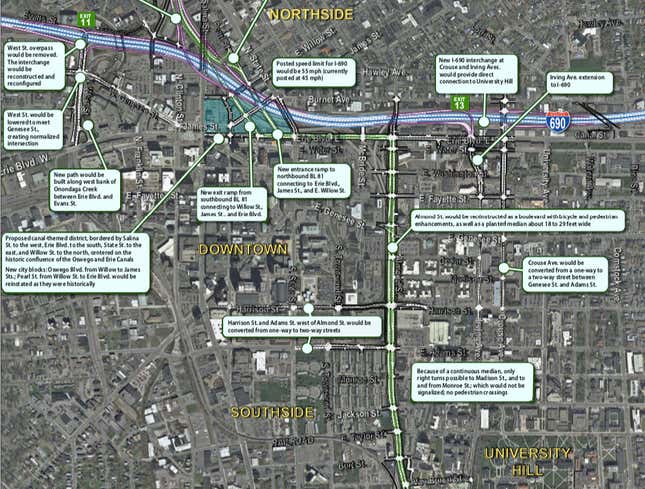

The other is to tear down the viaduct, replace it with a street grid, develop the land freed up by the erstwhile viaduct, and route those not going to Syracuse around the city entirely.

The “community grid,” as its been dubbed, reflects a new trend of urban development away from highways, de-emphasizing car usage to make streets more pedestrian, bike, and transit-friendly. While that sounds good to many on its face, it’s far from clear that the people who currently live there would stand to benefit.

Both experts and the people who live on the South Side fear that chopping down the highway and replacing it with a grid would open up the once cut-off neighborhood to gentrification, and force current residents out just as highway construction did.

“This is not just a transportation project,” said Lanessa Chaplin, the I-81 project manager for the New York Civil Liberties Union. “There’s a lot of civil liberties and civil rights issues ingrained into this.”

For the community grid to truly be effective, Syracuse must reckon with a legacy of transportation development that, as happened in many American cities, contributed to segregation, poverty and urban decay. It must wrestle with the reasons previous plans did not work. Or else, Syracuse risks simply repeating the injustices of the past.

In a sense, solving Syracuse’s I-81 problem will require the city to come to terms with what the highway destroyed.

By 1950, nearly 4,000 black residents lived in the 15th Ward, or eight out of every nine black people in all of Syracuse. By 1960, the 15th Ward’s population would more than double.

It was, of course, no accident that nearly all of Syracuse’s African-Americans were confined to one district. Before the ward was an African-American community, it was a Jewish one. African-Americans arriving in Syracuse quickly found Jews were the only people in Syracuse willing to rent (or sell) to them.

And the timing of Syracuse’s increasing African-American population came not long after the advent of redlining, the process by which the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a federal agency, marked any minority neighborhoods “hazardous” for loans in red ink. On the local level, realtors were only too happy to reinforce the HOLC’s boundaries, which codified long-standing norms discriminating against people of color.

In 1954, the Syracuse Post-Standard’s Walter Carroll published an influential 11-part investigation into the 15th Ward that simultaneously served as the main trafficker of the overcrowded slum narrative while also providing the frankest commentary on how discrimination and outright racism were the root cause of the conditions of the 15th Ward.

Part Seven—six parts after he reported on a wall of a 15th Ward house supposedly lined with “thousands” of cockroaches as its residents nonchalantly snacked—quoted two anonymous real estate agents extensively on their discriminatory practices:

“The way Syracuse real estate dealers discriminate against Negroes is this: Negroes are just not shown houses for sale… There is no out-spoken discrimination. It is a very subtle thing. If they get a Negro who wants a house they show him a house in the slum area or the semi-slum area and tell him that’s all there is.”

Another anonymous realtor told Carroll:

“I think they are entitled to good schools and hospitals, but you just can’t move them into white neighborhoods,” he said. “I would not tolerate colored people moving into white neighborhoods, and we definitely do not sell to them.”

With the exception of the 15th Ward, where rents and home prices were many times higher than elsewhere in the city despite the reportedly atrocious living conditions, black residents were locked out of the home ownership market just at the time when white Americans were increasingly abandoning cities and buying homes in the suburbs.

In the final installment of the series, Carroll recalls four officials from local and national home builders associations coming to his office with a solution. They didn’t want to fix the 15th Ward. They wanted to knock it down.

The fundamental concept of urban renewal was simple: some neighborhoods were not worth fixing. The term didn’t appear in Congressional acts until 1954 but began in earnest with the passage of the Housing Act of 1949, arguing that it’s better to knock down, start fresh, and reimagine the city anew, often with towering housing blocks, cultural centers, and business districts.

Such was the logic Syracuse officials pursued, not just with the 15th Ward, but other areas downtown, too. Grand renderings sketched out spacious plazas, modern architecture, and sleek highways. Planners imagined the city’s dilapidated housing stock replaced with new, mixed income housing. In essence, they thought Syracuse’s problems could be fixed not with new attitudes towards race and class, but new buildings.

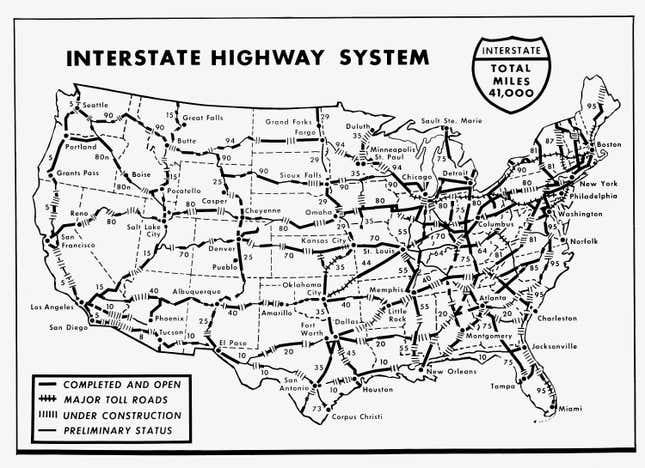

At nearly the exact same time, Congress also passed the Federal Highway Act of 1956, permitting the construction of tens of thousands of miles of interstates lining the country. Among other goals, cities dreamed up grand urban highways that whisked people to and through downtown with minimal inconvenience.

Transportation and housing are two sides of the same coin. Where you live and how many other people live near you determines how you move around. As more and more (mostly white) Americans left cities to live in the suburbs that lacked any public transportation, they did so through the cars they bought.

Cars, it turned out, picked up much of the manufacturing slack after American factories weaned off weapons of war. In 1945, there were 25.8 million registered vehicles; by 1955, there were 52.1 million; a decade after that, 75.3 million. But the construction of America’s highway network went hand-in-hand with suburbanization and white flight, each enabling more of the other, while both fed demand for the postwar car boom. The advent of the modern American car industry is inextricably linked to the discriminatory housing policies that facilitated suburbanization.

“When we talk about the interstate highway system, we talk about it from the lens of the time Eisenhower went to Germany and saw the Autobahn and he was impressed and he wanted to make sure we had something like that,” said NYCLU director Yusuf Abdul-Qadir, who took it upon himself to make the I-81 project a full-time focus for his chapter. “And we talk about it being a marvel and a feat of engineering and ingenuity and our ability to kind of get communities from Point A to Point B expeditiously. But we very rarely talk about it from the sense of how it became a mechanism to help drive segregation.”

As more and more people left cities, tax bases eroded, and so urban renewal became a critical method for cities to get federal dollars to try and stem the bleeding.

Although urban renewal and highway construction may sound like two separate policies, they were part of the same phenomena at the same time in the same place, in many of the same inner city neighborhoods around the country. Syracuse’s 15th Ward was one of those neighborhoods.

“They resulted from two different acts of Congress, but in essence they were doing the same thing,” said Norman Garrick, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Connecticut. “Because it was about a mindset at the time in terms of attitude towards cities and the role they would play going forward in American life.”

In Syracuse, planners initially wanted to dig a giant ditch through the city and run the highway below ground level, but they determined the water table was too low thanks to the nearby Onondaga Lake. And they couldn’t build it at ground level, because railroad tracks snaked across at one point. So, they determined, they’d have to build an elevated highway.

“It would be all right with me if they’d take it all,” one resident just outside the 15th Ward told a reporter in 1958 who canvassed the neighborhood to find out how they felt about a highway being built over their heads. “I don’t like the way the city is moving all these colored people in with us—they’d put them right in your living room if you’d let them.”

The city pretty much did take it all. Nine hundred people were displaced by the highway project, a quarter of that due to urban renewal in the city.

Many African-American activists, renters, and homeowners voiced opposition to both the highway project and “urban renewal” in general. They consistently argued that the challenges facing the 15th Ward were rooted in housing and employment discrimination, forms of institutional racism. Substandard housing, they consistently argued, would largely fix itself if African-American homeowners had access to the housing and lending markets.

In January of 1957, almost three years after the multi-part Post-Standard series and well after urban renewal began, dozens of speakers, mostly African-American homeowners, came out to a town meeting to oppose a $5.4 million project ($64 million in today’s dollars) that would require demolishing an unspecified number of homes and displacing the people who lived in them.

One of them, Amanda Hoffman, observed “Of course you realize how difficult it is for Negroes to get homes here. Negroes in this city have no place to buy homes. You know what our chances are of buying a home next to you. Why can’t you build this project and leave us alone?”

No amount of pleading or appeals to reason seemed to work. By 1965, more than 90 percent of the 15th Ward had been bulldozed. Most of its former residents moved to other areas of the city, Carroll noted in the Post-Standard.

Tellingly, nobody seemed to bother to follow up on the urban renewal project for quite some time. One of the only thorough de-briefs of Syracuse’s urban renewal effort in the 15th Ward while its practitioners were still alive was in 1974 by Lester Fredrick Volker II, an architecture graduate student at Syracuse University. Volker was able to talk to several of the officials involved in the planning and implementation of urban renewal, giving his report unique insight into the project no contemporary reporter could replicate today.

His findings were scandalous. “Something somewhere had gone wrong,” he wrote.

Areas were slated for clearance before anyone figured out what to do with the people who lived there. In some cases, entire neighborhoods were knocked down before they even figured out what they wanted to build in its place. Furthermore, they made “little attempt to provide adequate compensation for displaced families.” Despite given some “financial assistance,” Volker pointed out, “what really mattered was a place to live.”

Officials almost always offered families new housing far away from the 15th Ward. But families didn’t want to leave. And the State Department of Public Works, which oversaw the construction of I-81, charged the relocation office within the Office of Urban Renewal with finding new homes for the families the highway was displacing, as the two policies blended together into one.

The relocation office was short-staffed as it was when dealing solely with the urban renewal displacements. Adding another 900 people on top of that stretched their resources to the brink. They didn’t even have staff to survey the residents to ask what type of home they were looking for. In effect, many of these families were on their own to find new housing in the very same overcrowded areas, exacerbating the very conditions urban renewal was ostensibly trying to alleviate.

(South Side residents often spoke of a local legend that some families found out their house was slated for demolition by coming home to find a red “X” painted on their door, giving them mere weeks to pack up and leave. I could not confirm those stories, either through contemporary accounts or talking to former 15th Ward residents; the Office of Urban Renewal did, however, paint white “X”s on properties already vacated and slated for destruction to ensure the crews knocked down the correct house.)

Volker, who died in 2005, came away from his research concluding that the entire project seemed to have “came about after a few people got together one night and decided that since the area was so bad, something should be done. This resulted in slating the area for total clearance. As an afterthought the problem of relocation was considered.”

And it didn’t even work. “A ‘desirable neighborhood’ was not created,” Volker noted. But in the eyes of the former residents of the 15th Ward, one had been destroyed.

Indeed, Garrick and countless other experts—Jane Jacobs is often credited as being one of the first, with her landmark 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities—have pointed out that urban renewal and the concept of urban highways, joined at the hip as they were, had fundamental flaws.

Many conceptions of what a city would look like back then were unrealistic, imagining massive urban parks underneath even more massive highways. Few planners at the time reckoned with where all the cars would be kept in the downtown area while people worked or shopped or ate, a problem that created a vicious cycle as ever more parking replaced the very attractions that were supposed to lure suburbanites downtown in the first place, and even more cars created a street environment few people wanted to walk around. Soon, city officials found themselves managing downtown areas with ample highway access, plenty of parking, but few attractions to give workers a reason to stick around after clocking out.

Some go even further and have argued the very concept of urban renewal was flawed because it never articulated what success would look like. Historian Jon Teaford observed that all different kinds of special interests grabbed onto urban renewal to solve their respective causes, often in conflict with one another.

Downtown business interests wanted to save the city by creating more economic activity and highways, while mayors and city councils wanted to boost tax revenue. On the other hand, welfare and housing advocates wanted to help the inner-city poor by, among other things, building better affordable housing. Urban renewal could not have taken place without this unholy alliance, but in order to form a coalition, it failed to accomplish any of their lofty goals.

When push came to shove, the people with the least political influence suffered the most. That meant lower-income minority neighborhoods across the country. For instance, a Georgetown citizens group played a key role in opposing a highway plan that would have decimated much of Washington, D.C. (including some African-American neighborhoods, but also several predominantly white, wealthy ones). In New Orleans, the Riverfront Expressway was originally slated to run right through the French Quarter; that section never got built due to opposition, but the one through Claiborne Avenue, a predominantly African-American neighborhood, did.

In New York City, Robert Moses infamously unleashed a highway building bonanza, including massive land takings and neighborhood destruction in the Bronx. One of the few he never managed to build was the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have gashed a scar across iconic neighborhoods and Washington Square Park.

“I think there was a strong racial component to it in all the policies of that era,” Garrick said. “Even if it was not overtly stated, you look at the impacts around the country and you can see the impacts were disproportionately on racial minorities. And it’s not just one city. It’s city after city after city around the country.”

After studying what to do with the viaduct for the better part of a decade, in April the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT), the agency in charge of the I-81 project, released a 15,000-page draft of their final report. They recommended the “community grid” option. By law, NYSDOT must solicit comment from the public before issuing a final decision for federal approval.

Now, 60 years later, as Syracuse embarks upon a mega-project that’s a direct descendant of the first, an eerily similar alliance threatens the community grid alternative. Community advocates like NYCLU have, for the moment, joined forces with downtown business and real estate groups, reflecting some of the same alliances that got behind urban renewal.

Their visions of a post-viaduct South Side overlap—a prosperous mixed-use neighborhood adjacent to Syracuse University, Upstate Medical Center, and downtown Syracuse—are also rife with potential conflicts. When Chaplin canvasses the neighborhood surrounding the viaduct, one of the most common concerns her neighbors express is that of gentrification.

Experts agree with their concerns. Ben Crowther has been studying urban highways for years at the Center for New Urbanism. He manages their Freeways Without Futures initiative, which looks at what to do with urban highways nearing the end of their useful lives around the country.

“The removal of the highway has the potential to essentially repeat the same outcomes that the construction of the highways had,” Crowther said. The viaduct has acted as a border that prevented the more gradual flow of economic opportunity seeping outwards from the university, downtown, and hospitals in recent years. Once that barrier is removed, residents expect it to cause a shockwave of higher property taxes and rising rents, which current residents are unlikely to be able to afford.

Hovering over all of it is the history of the 15th Ward and the South Side. Supporters of the community grid say this history must be taken into account when deciding what to do with the viaduct. Those who oppose the grid rarely talk about race, instead preferring to focus on pretty much any other topic.

“We just have to start calling these things out,” Chaplin of the NYCLU said. “This undertone of racism needs to be addressed. [Some] people who live in the suburbs, not all, have this fear of coming into the city. And a lot of it is they don’t want to drive in the city. They think if they drive in the city, right, they’re driving into a black neighborhood. Therefore, it’s dangerous. And they don’t want to have to get off the highway and drive through a black neighborhood to get to work.”

Chaplin isn’t the only one who believes this dynamic is at play. Kerin Rigney, a town councilor in DeWitt just outside Syracuse, has caught a lot of flak as one of the few suburban politicians vocally supporting the grid plan as a remedy for historic inequalities. “Our number one problem here is racism,” Rigney told me one morning in a health food cafe over coffee. “I think that if we look at all the decisions that are made or all the things that are ignored, a lot of it has to do with racism.”

Minch Lewis is one of those people who worked to save downtown Syracuse at a time when, in retrospect, all the policies were working against him. He sees that now. “We lost,” he lamented on a pleasant May afternoon as he drove me around. “Everything moved to the suburbs.”

As we motored down street after street, by public housing, university parking lots, and a university steam plant that the city OK’d right next to the viaduct in the part of town it was ostensibly trying to save, Lewis would point to a vacant piece of land, or a property with an abandoned house, and say, see? Didn’t work.

In 1966, Lewis worked for the Metropolitan Development Association after moving from Chicago, before he ran local housing projects and then became the Syracuse city auditor. He doesn’t buy the argument that tearing down the viaduct and replacing it with a street grid will bring back the 15th Ward. To him, building a mixed-use neighborhood where the viaduct currently looms is an attempt to repeat the same strategies as the past, the same ones that didn’t work when he was trying to save downtown.

I came to meet Lewis through an organization called Save 81, an opaque group without any public leadership structure that on multiple occasions refused to discuss its origins, where its money comes from, or even identify who was responding to my emails. On its website, the group claims to be “a diverse coalition of concerned citizens, elected officials, residents, employers, union members, and community groups that opposes this boulevard option.” But the website’s “Members and Supporters” page is blank, offering the reader only that it is “currently being updated,” which has been the case since I began reporting this article in April. The group does not file any type of non-profit tax forms with the IRS, nor does it appear in any lobbying or campaign financial disclosure records with the state of New York.

But a 2015 update sent to members includes a letter to the Federal Highway Administration and the NYSDOT signed by Anthony Mangano, who, along with his cousin Carmen Emmi Jr., own at least nine hotels in the Syracuse area, including several near I-81. The letters list Save 81’s address as the same location as the Holiday Inn they own at the I-81/I-90 junction. The signatories to the 2014 letters are almost all business interests or politicians from outside the city.

Also opposed to the grid plan is The Pyramid Companies, which owns a large mall somewhat hilariously called Destiny USA just off I-81. Destiny USA is not doing so hot, just as many suburban-style indoor malls are faring poorly thanks to competition from e-commerce. Experts generally agree that the grid plan won’t actually hurt Destiny USA, but that hasn’t stopped The Pyramid Companies from hiring one of the top transportation lobbyists in the country to fight the grid in Washington.

Whoever is behind Save 81, the group argues the grid will result in unacceptably longer commute times, potential loss of tax revenue as a result of less through traffic, and, as one member contended, longer trips to the hospital in the event of emergencies.

However, the NYSDOT disagrees. It predicts minimal impact on travel times, ranging from no change to a few minutes per trip depending on the origin and destination.

This fact is not lost on the people representing the South Side in city politics. Hudson, who grew up in the 15th Ward, is now the president of the Syracuse Common Council. She told me a story of being in line at an event about I-81 and overhearing a white woman express concerns about that very issue. Hudson found herself thinking, “People live here,” meaning right around the viaduct. “How do you not know that?”

But Save 81's Lewis never brought up commute times. He has plenty of other concerns, which he was happy to share with me over the course of several hours. Mainly, he doesn’t believe replacing the highway with a community grid would spur development as many of its proponents hope. He rejects the idea that I-81 contributed in any meaningful way to segregation and poverty. And he doesn’t buy into the idea that having an elevated highway creates any kind of physical barrier to movement.

As we passed Wilson Park, with several basketball courts practically underneath the highway, he opined, “For us suburban white middle-class suburbanites, this is pretty ugly. But, you know, if you want to play basketball in Wilson Park, hell, you just walk across Almond Street,” by which he meant the road directly underneath the highway featuring 40 mph two-way traffic and traffic lights timed for car traffic, not pedestrians.

When I asked about the health implications of having children play right under a highway with cars and heavy duty trucks constantly roaring just overhead, Lewis had an answer for that too.

“Instead of removing barriers, it’s going to put a tremendous number of cars in this neighborhood,” Lewis contended, as traffic is moved from the highway to the neighborhood streets. “Bad news.”

It’s a line I’d heard from other I-81 supporters, but it’s one NYSDOT’s analysis again doesn’t agree with. It fails to account for the diverted traffic that will loop around the city and no longer pass through the neighborhood (ironically, this diversion of traffic Save 81 fails to account for in this context is the basis of their argument for lost business income and tax revenue). NYSDOT projects about 12 percent of all I-81 traffic will be diverted around the city under the community grid plan, including 65 percent of northbound truck traffic in the mornings. NYSDOT’s environmental impact analysis further found that the community grid would have lower emissions and particulate matter throughout most of the neighborhood than the viaduct option.

Yet Colleen Gunnip, town supervisor for Salina just outside of Syracuse, believes the community grid would be worse for the South Side and for the entire region. She told me she thinks NYSDOT have wanted to do the grid all along because it’s just cheaper than rebuilding the viaduct.

“I kind of feel as if they already had a preconceived notion of what they were looking to do,” Gunnip said recently, calling all the community meetings with large maps, printouts, and NYSDOT staffers on hand to answer questions “a dog and pony show.”

Mark Frechette, the I-81 project manager for NYSDOT, says yes, the grid would be cheaper than the other options, but adds there are other benefits, too: construction would not last as long, it doesn’t require taking anybody’s home, is better for the environment, and frees up prime real estate adjacent to major employment centers for development, which would add to the city’s tax base rather than detract from it.

When I asked Frechette if NYSDOT has preferred the grid since the beginning as Gunnip suspects, he replied that his office thoroughly considered all options and is recommending the grid because they believe it to be the best choice. He added that some groups have been making his office’s job harder by spreading disinformation. He didn’t name a specific group, but an example he gave had to do with a common anti-grid falsehood that claims the diverted traffic to the loop around the city will cause asthma in areas several miles from the highway due to increased traffic. To anyone who thinks NYSDOT has an alternative agenda, Frechette asks them to “look at the facts.”

Meanwhile, South Siders had a hard time trusting the government because of their own experiences with discrimination and the history of the 15th Ward. Pierce-El summarized the trust issue as: “We have been bamboozled for so long, you know? Not just from African American politicians but politicians in general. They start something, they tell you what they’re going to do, but then in the end, they disappear.”

Hudson, although a politician herself, expressed similar sentiments. “We’re talking about a community that’s beat down. We’ve been beat down for decades. And when you have a community that has just been beat to the point where they just can’t be beat anymore...” she trailed off, before punctuating, “We’re humble people.”

In fact, South Siders are often taken aback by Chaplin’s question of what they would want out of the project. One man at a weekly community workshop held by NYCLU answered the question by rambling, “I don’t even know how to ask what should be done, you know what I mean? I don’t even know where to go. The information that you just told me, the information you just gave me, I wouldn’t know how to say what to ask for.” Chaplin later told me the most common requests she gets are for air conditioners.

This is in stark contrast to Save 81’s ask, which countered the rebuild vs. community grid choice presented in 2015 with a third “hybrid” option to dig a tunnel for through traffic while building a grid on top of it. They successfully lobbied Governor Andrew Cuomo’s office to fund a multi-million dollar engineering study of the hybrid option, which found it technically possible to do, but NYSDOT later determined it would cost an estimated $4 billion, more than twice as expensive as each of the other options ($1.4 billion for the community grid and $1.7 billion to rebuild the viaduct). In other words, their “ask” was for at least 2.3 billion additional dollars, mostly from the federal government.

Lewis considers this additional price tag yet another plus of the hybrid plan, since, in his mind, more federal dollars means more jobs. But, without major structural changes to the way workers are hired on large construction projects, the thousands of middle class jobs on any of the viaduct alternatives will likely exacerbate historical inequalities rather than mitigate them.

A report by the non-profits Urban Jobs Task Force and Legal Services of Central New York looked at four recent large construction projects in the Syracuse area and determined on project after project, close to 90 percent of the workforce was white. On the I-690 project, another Syracuse highway project, 87 percent of the workforce was white, and 88.8 percent of the hours worked by African Americans were for lower wage, semi-skilled work. In comparison, Syracuse has a 49.5 percent minority population.

Project labor agreements with diversity requirements could be part of the I-81 project, but it would require rigorous enforcement and changes to the way union membership and apprenticeship programs work.

The Urban Jobs Task Force has been fighting for such an agreement with the I-81 project, but many South Siders aren’t aware this is even something they can (or should) demand.

Not long after Lewis’s drive around the neighborhood, I followed the NYCLU as they went canvassing, where Chaplin was updating people in the neighborhood on the I-81 project and how to tell NYSDOT about their concerns. NYCLU’s main goal is not to advocate for a specific outcome—although they readily admit the grid fits better with their organization’s mission—but to keep the South Side engaged and involved in the process.

Chaplin, who grew up on the South Side, often tells her neighbors that NYSDOT’s first public comment period after the grid vs. rebuild alternatives were announced, only 12 of the 1,200 comments were from South Siders. (Frechette demurred at that count: “I don’t know how they arrived at 12 from the South Side,” he said. “We held numerous meetings in the South Side and I’d be surprised if we only got 12 out of the 1,200.”)

This statistic—like the oft-repeated notion from Save 81 faction that the 15,000 page report did not include the towns of Selina or Cicero—is yet another salvo in the long battle over who has been ignored the most and, by extension, who should be listened to now.

Back on the canvass route, at a house not 100 feet from the highway, Anthony Broadwater was grilling chicken and bacon on his grill. The small group chatted with him about the highway project for a bit as he offered us some bacon chunks (Full Disclosure: I ate one, and it was delicious). He said he didn’t know much about the I-81 plans and he would think about coming to the next NYCLU meeting at the local library branch a short walk away, but sounded non-committal. Referring to NYSDOT, or the government in general, as he waved at a cop car driving by, he predicted, “They’re gonna do what they’re gonna do.”

For people like Broadwater, for whom the highway is a constant background hum to their daily lives, it can be hard to imagine anything will change. Syracuse has been arguing about whatever shall be done with the viaduct for almost a decade now.

Perhaps the most common sentiment I heard about I-81 is that, more than anything else, the debate has been interminable, which makes it harder to keep people like Broadwater engaged.

Now, NYSDOT will review the public comments gathered at meetings held over the last two months, make any changes, and then issue a final environmental impact statement with its preferred plan. Then, it will coordinate with the Federal Highway Administration to issue a final, final decision.

There is no deadline for this, but the general expectation is that this process will take at least the rest of the year. There is no hard plan for when construction will begin.

Shortly after Chaplin wrapped up canvassing, I went downtown before heading south to leave town. I went the way most people do when driving south: over the viaduct. Had it not been there, my exit from Syracuse may have taken, by NYSDOT’s estimate, approximately one minute longer.

I stayed in the right lane, trying to spot the houses I had just been to with the canvassers. But, thanks to the elevated structure, I had to look down to catch a glimpse. The sumptuous smell of Broadwater’s grill that wafted around the neighborhood for seemingly hundreds of feet in every direction was undetectable.

Speeding by at 60 mph and faster as you leave town, you have to try to notice the South Side even exists.

Correction 4:22 p.m. ET: A previous version of this article stated Chaplin still lives on the South Side. She currently lives in Eastwood.

This story was originally published on July 30, 2019