The tiny racing truck tore back off into the night, and we were left looking at each other. Jams and Boothe had caught up to us, being chauffeured in a chase truck by another friend. They looked brain-dead; I recognized their exacerbation from the last time I ran this race. They’d be human again in a few days.

For now they weren’t in shape to much more than sit and stare vacantly. I couldn’t help but ask: Why was I doing this to myself again?

(Full Disclosure: Last November, I raced the 50th Baja 1000 with personal friends of mine who operate the Desert Race School and other off-road related companies. They covered most of my expenses while I was in Mexico with them.)

The sun was only a couple hours from rising as Ron Stobaugh—veteran desert driver, leader of our motley crew, and Baja winner himself—and I saddled back up and proceeded south again for our chance in the race car. We didn’t get more than a mile down the road until we heard trouble on the radio.

“…Bad trans…” came through, between crackles and pops of the garbled radio transmission. “…overheated transmission…”

Through more strained communication we figured out that our race car was immobile. It’s not the most complicated piece of machinery: a compact tube frame fitted with long-travel suspension and a 2.4-liter General Motors four-cylinder engine pushing something like 200 horsepower to the rear wheels through a manually-shifted three-speed automatic. Was its transmission really borked or was the truck just stuck in sand?

Stobaugh, now 20 hours without sleep, was quickly losing his trademark composure as we tried to solve the new problem using phones and radios, both of which seemed to half-working.

That meant I had a new problem, too. Looking after the driver is as important as looking after the car, and the onus of both falls on the co-driver. But who was I to tell a man more than 20 years my senior, with thousands more hours in Baja, to chill out and relax?

I only got out of this dilemma by luck, or fate. One of our support crews had been able to get to the race car and get it freed. Apparently the failing transmission had been misdiagnosed, and the mood snapped from tension to giddiness as we watched our guys claw back time and make passes via satellite tracking.

The guy behind the wheel was a rookie at Baja but a pro in a race car: Loren Healy, a sponsored driver and known name in off-road racing. Within an hour we were leading our class. And then I had another new problem.

After I reported our race car’s position, Stobaugh looked sternly across our chase truck’s hood. “If we get the car in the lead,” he said “we’re gonna have to be, fucking, on it.”

Great, another layer of pressure. I tried not make it too obvious that my first thoughts were fearful ones.

“Hell yeah,” I lied.

San Ignacio is a quiet waystation about halfway down the Baja peninsula, home to one ancient church, a bus stop, and one of the few decent cups of coffee for miles. We were posted up at an inn waiting for the kitchen to open to get a caffeine bump before Stobaugh and I would take the race car through the third quarter of the Baja 1000.

The sun was up, but the morning cold hadn’t burned all the way off yet. I was already wearing my borrowed Santa Claus-red racing suit to keep warm and, of course, look cool. What was the point of coming down here if you weren’t going to play with the toys, right?

If it’s hard to imagine being able to hang out and casually sip coffee while you’re waiting on a race car to show up, believe me, being awake for 24 hours will sap the adrenaline out of you in any situation. At least, until one of the other co-drivers I knew caught up to me and gave me a shakedown of what to expect in my section.

“What did you guys see on your scouting run?” he asked. I told him I hadn’t had time to join the prerun this year.

“Oh, dude.” The look on his face drowned me under yet another cascading wave of anxiety.

“I thought this part was supposed to be pretty smooth,” I replied, praying that saying it would make it true.

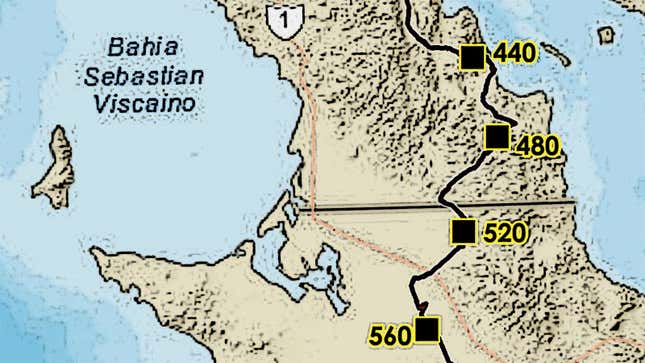

“Dude,” he said again, whipping out a topographical map on an iPad. “This part is smooth,” his finger ran across a short map line near our current position. “This part is jacked up. And this spot, this right here, make sure you stay right, as far right as you can, or you’re going to be digging through silt all day.”

More tips. More notes. I thought about writing them down, but realized I’d have no hope of referencing a piece of paper from the carnival ride that is a race car at work.

Speaking of which… where was that thing?

Stobaugh and the rest of the support team were already working the radio. Our car had fallen behind all our competitors and been sitting static 20 miles north of us for way too long. A supercharged Ford Raptor was dispatched to drag the car out of the dirt, which was a bad sign.

It was looking like our race might be over before I even had the chance to compete. And though I’m a little ashamed to admit it, part of me was relieved.

But as appealing as the idea of sleep was, there’s no way you can drive halfway down Baja and not do your damnedest to finish.

The problem was identified as a pump seal in the transmission. It seemed that excessive heat had caused it to break, which resulted in the TH350 automatic puking its lubricating fluid and seizing. The team was convinced that if a new pump seal and more transmission fluid could be found, the race could be saved.

On top of that, there was another carcass of a race car identical to ours marooned right next to us, and its owner was willing to sell us parts off it. (Yay!)

Unfortunately, it had experienced the exact same pump seal failure. (Fuck!)

With the race car towed to San Ignacio, some set to wrenching on it, others worked on the new donor, and I, as the only member of the group with a vague command of a few Spanish phrases, was elected to scour Baja for a new pump seal.

Renewed purpose reenergized me. I grabbed the keys to a Silverado work truck we’d brought but my first stop was the bar. “Are there any auto parts places around here?”, I asked the guy who’d sold me coffee, knowing he spoke English. There was, down the street, but for transmission parts I’d need to go to another town: Vizcaíno.

The other co-driver I was talking to earlier overheard its name and shook his head gravely. “That’s 50 miles back, dude.”

I tried the local joint first, which wasn’t so much an auto parts store as a roof and three walls, all of which were bristling with serpentine belts and old-looking tools. “¿Hablas ingles?” No. “Ah, tengas partes para transmisiónes?” No.

The man at the shop said something else, but all I recognized was the name of the town the bartender had said.

“Looks like we’re heading to Vizcaíno,” I said to Jams, who had recovered from his experience in the race truck enough to keep me company on my search.

The sun was blazing as we tore across open highway, backtracking on a section Stobaugh and I had come through in the dark. That felt like three days ago, though it’d only been a few hours. I realized I had now passed 25 hours without sleep. I slowed down.

Vizcaíno is little more than an intersection in the middle of an endless valley, dehydrated and dusty. A few industrial structures make a short and square skyline. Ads were painted on the sides of buildings. Battle-weary big rigs lumbered through the miniature Mos Eisley as we landed in the big auto partes.

I stormed in, computer in hand, open to a Word doc of Spanish car repair phrases and a web page describing the TH350 transmission I’d opened on WiFi.

Again, “¿Hablas ingles?” No. “Ah, tengas partes para transmisiónes?” I showed the computer screen to the man behind the counter who was squinting in confusion. “Necessito gaskets y SEALS para Tea-ache tres cinco cero,” a phonetic butchering of “TH350.” I couldn’t remember how to say “three hundred” or “50” and hadn’t downloaded that piece of vocabulary. I felt bad. I was doing the best I could. But what we had did the trick.

¡Si! the man went back into what looked like a store room, and I glanced around the shop in awe. The walls were chockablock with cool vintage parts. Beautiful chrome fog lights with yellow lenses, a Radwood period-correct head unit in a faded box, a big “DATSUN 4x4” windshield banner. “Man, we gotta come back through here when we’re not racing. Look at all this cool crap!” Jams was less amused, more barely conscious.

Before I could take a closer look around, the shopkeeper emerged with a giant bag full of gaskets and seals of assorted sizes. On the UPC sticker, “GM TH350 GASKET KIT.”

Fucking jackpot.

I didn’t bother converting the price from pesos to dollars, I just gave the man a wad and sprinted back to out Silverado, believing I was going to be a hero in our Baja story.

By the time I got back, our race car was dismantled in the dirt motel parking lot.

Greasy arms and bloody fingers were flying over metal while tired eyes looked on anxiously. I dropped the “TH350” bag on the deck and Chris Corbitt, Nitto Tire PR guy who’d been co-driving with Healy, pursed his lips to say “not bad.”

I collapsed into the shade and started chugging water, remembering that this victory only meant I’d have to go back into the fray with a tired driver and a beat-ass race car. But there was no need to get worked up over that.

Work continued until it didn’t. Everyone went quiet. Bodies ground to a halt. Healy trudged over to where Stobaugh and I were cooling our heels.

“We don’t have it,” he said flatly. What? “What you got is, like, a transmission rebuild kit,” he responded to the heartbreak I was most assuredly wearing on my face. “There’s no pump seal in here.”

“Guh, god-damn it.” I stammered, ripping through the stages of grief at breakneck speed. “I was so sure I told the guy, every seal for a TH350. Are we… are we sure…” I trailed off. If Healy said we didn’t have it, we didn’t have it. I felt about as worthless as the puddles of refried red transmission fluid we were standing in.

Stobaugh wasted no time on rage or sadness. At least not outwardly.

“Alright,” he said, sounding surprisingly awake. “We’re calling it.”

Aluminum cans cracked. Rooms at the hotel were ordered. The team sipped their sorrows away in the company of our race car’s corpse. The mood fluctuated between disappointment, anger and relief that the craziness was over. Those first two emotions burned out the quickest.

“Dude, you did damn well finding those gaskets at all,” Corbitt said to me. He followed up saying something like “everybody gave this their best, and going home knowing that is all that matters.”

I had a long, long ride home to think. This was my fourth time on a desert race team, and my fourth DNF. Why do we do this? Why, after all that heartbreak, would I ever want to do this again?

I was really hoping to have a neat and tidy epiphany or a moral to this story, but the fact of the matter is, sometimes you try and try and just fucking fail.

This is what adventure racing’s like in the desert. It sucks, it’s difficult and it’s dangerous. And if winning it were easy, it wouldn’t be worth shit.