About this time every year, car enthusiasts rejoice over what 25-year-old cars they can now legally roll onto a ship and bring to America. The reason a Renault Avantime, R34 Nissan Skyline, or S15 Nissan Silvia remains forbidden fruit is this infamous “25 year import rule.” It wasn’t always this way. Decades ago, just about anyone could import a foreign car and get their “gray market” vehicle federalized. But what you think you know about this law may be wrong, so let’s dive in.

The Imported Vehicle Safety Compliance Act of 1988 became law in the winter of 1988, effectively banning the import of vehicles under 25 years old that didn’t comply with American safety and emissions regulations. This law still has a grip on car culture today, preventing enthusiasts from buying cars too strange, too interesting, too niche to ever be offered in this country.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has a page dedicated to vehicle importation, and you could spend days getting lost learning the various ways the federal government doesn’t want you to bring a car here that does not meet our Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards or Environmental Protection Agency regulations.

Those who have tried to circumvent the rules have often found their cars at the business end of a crusher. The government has a knack of filming the demise of those vehicles.

If you’ve read my stories last year you probably know that I went through the process of importing a car not just once, but twice. And this is after I already owned one of the few gray market imports that can be imported under the 25 year rule. Ever since then, I can’t look at a Japanese or European car for sale online without thinking, “just how did things get like this?”

Some enthusiasts and even some websites point the finger at Mercedes-Benz and a quest for money, but there’s more to it than just that.

Take A Trip To The Past

To truly understand how we got here, we must rewind our calendars back to the 1970s and 1980s. Japanese compacts started to fill shopping mall parking lots after not one but two oil crises, and German sports sedans started to clog up country club valets as the rich eschewed American luxury. If you turned on “Dallas” in the 1980s, you saw Bobby Ewing in a Mercedes convertible, not a Cadillac. In Back to The Future, the good guy drives a Toyota. You could meet the friendliest people on a Honda or look like a diplomat in a BMW.

By the 1980s, Americans couldn’t get enough of imported goods. In 1989, the Los Angeles Times looked back on America’s insatiable lust for shopping during the decade. Everything from microwaves to watches, computers, espresso machines, video games and more found their way into the American household. Many of the goods during the buying craze were imported, including lots of food.

Motorcycles were the canary in the coal mine. You’re probably well aware of what happened after Japanese motorcycles hit the market faster than Harley-Davidson could wrap its head around. Japan was importing so many motorcycles that Harley-Davidson begged the U.S. government to do something about it. In 1983, then-President Ronald Reagan signed the Memorandum on Heavyweight Motorcycle Imports, which levied tariffs on heavyweight motorcycles. They didn’t compete with the bar and shield, as RevZilla notes, but it was a sign that America was willing to get aggressive in these kinds of cases.

Import Panic

The incredible influx of imported goods and the value of the dollar relative to other currencies also encouraged a way to score technology, luxury items and even cars for rock-bottom pricing.

It wasn’t long before merchants found out that a television on the shelf at a store in America could be purchased for much cheaper in another country. Those merchants then scooped up those devices, imported them to the States, then sold them for cheaper than products sold through official distributors. These are what is known as “gray market” goods: products sold through unofficial channels.

The savings were often dramatic. A 1990 legal review noted that retailers like K-Mart were selling gray market goods for up to a 40 percent discount over goods imported through official means.

If you were shopping for an imported car back then, chances are you would have seen advertisements claiming that you could save thousands of dollars by buying directly from Europe rather than buying from an official distributor.

The gray market for cars has its roots back in the late 1960s when the federal government introduced the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966. This mandate paved the way for changes in vehicle safety design. Soon, vehicles were required to have specific safety equipment to meet American standards. Meanwhile, the government eventually required cars to have measures to reduce pollution.

Vehicles built in places like Germany didn’t originally have the equipment and systems required by the U.S. government. Unlike today, where converting a car to meet regulations is a huge, time-consuming, and expensive process, just about anyone could import and convert a car back then. Gray market vehicles needed to have U.S. compliant bumpers, door beams and fuel systems added. European cars in those days didn’t have catalytic converters, so those needed to be added, too.

This soon led to a market where buyers could get a vehicle from a seller who advertised sometimes shocking discounts new vehicles. Even dealerships sold gray market vehicles, undercutting their own brands.

A November 1985 issue of Kiplinger’s Personal Finance noted that a Mercedes-Benz 500 SEL could be purchased from a U.S. dealership for $53,000, but another 500 SEL purchased from a gray market source could be as much as $11,000 cheaper. That’s a decent chunk of change, but it’s even more when you realize that’s the same as getting a $30,000 discount on a $140,000 car.

It wasn’t just about saving money, either. If the manufacturer didn’t offer an option or an engine that you wanted in America, you didn’t have to just deal with it. Maybe BMW didn’t want to spend the money making its turbocharged 745i meet American emissions standards. BMW never officially sold that model here. That didn’t mean you couldn’t buy one. You could find another dealership, importer, or reseller willing to buy what you wanted overseas, then bring it here, throw a catalytic converter in it, and call it a day.

Just like with televisions and kitchen appliances, the demand for gray market cars was huge. Kiplinger’s notes that between 1980 and 1985 some 65,000 gray market cars have been brought into the States. 1985 closed out with 66,879 gray market vehicles imported.

A December 1984 issue of the Washington Post detailed just how big of a splash the gray market was making. At one point, more than 20 percent of Mercedes-Benz’s market in the United States was gray market cars it was not selling. Per WaPo:

According to Department of Transportation records, Mercedes-Benz accounted for 64 percent of the imports this year; BMW and Porsche, 11 percent each; Ferrari, 3 percent; Rolls Royce, 1 percent; and others, 9 percent. There is no breakdown between new and used cars, but a spokesman said that this year, new cars have become predominant.

That works out to about 22,000 gray market Mercedes-Benz cars this year compared with an estimated 79,000 cars imported through franchised dealers in 1984. In the past year, imports by Mercedes-Benz franchisees rose about 7 percent, but the number of gray market Mercedes-Benz autos rose more than 150 percent.

The gray market frenzy quickly became a major issue with the official U.S. distributors of the televisions, appliances and cars getting through the border through unofficial means.

Mercedes-Benz in particular made stemming the flow of gray market imports one of its goals.

Multiple Problems

The problem for the manufacturers of these products and vehicles wasn’t just one of losing money. Indeed, these companies weren’t happy that a distributor in another country was making a sale that they could have made, but there was more to it than that.

When you bought a gray market Mercedes-Benz, the car you were getting had the same badging and was often for the most part the same model sold by Mercedes-Benz of North America. However, the gray market Mercedes-Benz 500 SEL you owned was never authorized to be imported or sold by Mercedes-Benz.

On the surface, that’s not a big deal. You don’t get the warranty you’d get buying from an official channel, but in exchange you got a cheaper car that maybe had an option or a few that you couldn’t get from a dealer.

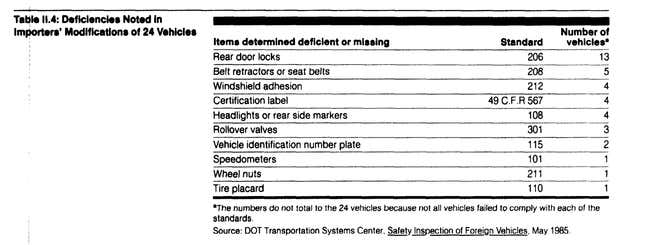

One of the problems came from the conversion process for a gray market vehicle. Just about anyone could do the modifications needed to make a gray import legal and it was on the owner of the vehicle to prove it met federal requirements. Proving it was all on paper and the car was never inspected.

Unfortunately, the quality of such modifications could vary wildly between a legitimate converter or importer and someone cobbling cars together out of their garage. This industry was unregulated and the government didn’t track or even inspect the firms and people who modified gray imports.

In the mid-1980s, Mercedes-Benz of North America started purchasing gray market imports to see how well the conversions were done. What it found was surprising. Here’s an excerpt from a November 1985 issue of the Chicago Tribune, where then Mercedes-Benz of North America spokesman A.B. Schuman shared what they found:

The vehicle reportedly carried papers certifying that it met U.S. safety and emissions laws.

The irregularities were numerous, he said, starting with the fact that the car was sold as a 1985 model 500SEL, when, in fact, it was a 1984 model. The car was identified as having an air-bag restraint system, but the equipment wasn`t installed. The car had a side-door guard beam to protect occupants in an impact, but the beam was a piece of tubular steel—already rusted.

Another problem was the positioning of the catalytic converter, which had been added to make the car conform to emissions laws. The converter is a muffler-like device that chemically changes harmful exhaust emissions to harmless vapors. The heat inside the converter is intense. In the gray market car, the converter was located only an inch from the car`s fuel tank, rather than the normal 14 inches.

Mercedes-Benz and other automakers saw the problems with shoddy conversions as tarnishing their brand image. After all, if someone unknowingly purchased a gray market vehicle and it broke down, Mercedes feared they’d blame the only entity they know to blame: the brand right there on the car’s badge.

Official dealers said they were also worried about liability suits stemming from potentially bad gray market vehicles, according to a Washington Post report, that neither they nor the brands they sold for had a hand in importing and converting. Dealers agreed with the automakers that gray market imports were bad for business.

The Automakers Had Backup

In 1986, Mercedes-Benz’s findings were supported by a U.S. Government Accountability Office (the GAO, formerly General Accounting Office) report titled “No Assurance That Imported Gray Market Vehicles Meet Federal Standards.”

The goal of this report was to examine the manner in which NHTSA, EPA and Customs carried out their duties in regard to vehicle importation. It also looked into government and auto industry studies that sought to find out just bad things were with conversions not being completed properly.

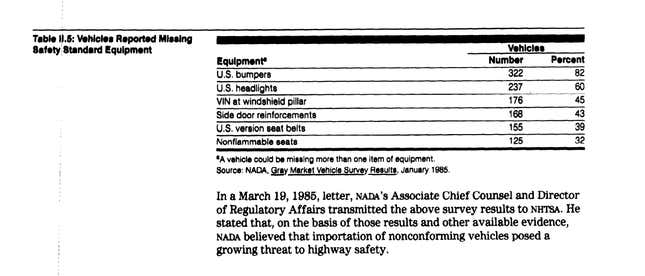

The report aggregated studies conducted by the Department of Transportation, the National Automobile Dealers Association, the California Air Resources Board, and Mercedes-Benz. GAO noted that these studies suggested that 50 to 95 percent of non-conforming vehicles imported into the country either weren’t modified to meet standards or the modifications were inadequate.

The office conceded that it did not examine the adequacy of the scope of the studies or their methodologies. However, the results still provided very official backup to Mercedes’ and its dealers perhaps financially-motivated concerns.

The report also included NHTSA testing, where two gray market vehicles were randomly purchased. Both of the vehicles failed to conform with a number of standards. Perhaps more importantly, both cars failed to meet crash standards for bumper strength. One of the vehicles also failed the standard for fuel system integrity when a fuel line broke during the crash test.

The GAO concluded that the NHTSA, EPA and Customs lacked the internal controls necessary to regulate vehicle importation. Its recommendations included that firms be certified to do the modifications on gray market cars and their work be periodically inspected. The GAO noted that there were existing bills in both the Senate and House at the time that offered variations of these recommendations.

This report, along with the aforementioned studies, set the stage that gray market cars were not just an issue of money or liability, but of safety as well. Backyard operators putting catalytic converters only an inch from fuel tanks put drivers at risk, and others simply lied that their vehicles conformed. For the automakers, the solution was clear: Gray market imports had to be stopped.

Not everyone was on the same page.

The Battle For Gray Market Cars

In 1985, a bill landed in Congress proposing to make the importation of non-conforming vehicles illegal, as the Orlando Sentinel reported at the time. (Florida’s status as a hub of questionable imports goes a long way back.) Its supporters included Mercedes-Benz of North America and the American Automobile Dealers Association.

As automakers and the AADA lobbied to stop gray market imports, the vehicle importation industry and even many of the automakers’ own franchised dealers fought back, offering an alternative.

One of the groups fighting against an importation ban was the Automobile Importers Compliance Association. It was a non-profit trade group consisting of about 200 importers, shippers, modifiers and testers.

I spoke with Dan Kokal, former Compliance Coordinator for the Automobile Importers Compliance Association.

He spent six years with AICA with his feet on the ground fighting to keep importation alive. Today, he runs Private Vehicle Imports, an importer that more or less specializes in seemingly hopeless cases. His site proudly proclaims “No Matter What You’ve Been Told There May Be A Way.” Kokal uses his unique experience to do what other importers say is impossible.

He explained to me that AICA wasn’t just fighting the automakers to keep importation going, but it pushed back against the very backyard conversion operators, chop shops and dealerships that didn’t follow the rules and didn’t go quality jobs. A Mercedes with a shoddy conversion didn’t have the potential to hurt just Mercedes-Benz, but the import industry, too.

Indeed, in those same reports where Mercedes-Benz North America and some of its dealerships show concern about diluting Mercedes’ brand identity, AICA was right there agreeing that bad conversion jobs are terrible for everyone. In a March 1985 New York Times report, Benjamin Jackson, then executive director of AICA criticized Mercedes-Benz for keeping prices high despite a strong dollar. At the same time, Jackson agreed that not all conversions are equal:

Official importers have sought to use the Federal emission and safety rules to block the gray market models. Most European cars, for example, have composite headlights rather than the sealed-beam lights required in this country.

The importers contend - and Mr. Jackson agrees - that some conversions are slipshod and fail to meet the Federal standards.

‘’Sure, there are some absolute crooks out there,’’ he acknowledged. ‘’But there are plenty of authorized dealers who roll back odometers and play bait-and-switch games.’’ Mr. Jackson said the association is trying to develop self-policing to control abuses.

Part of that self-policing was the 100-page Handbook of Vehicle Importation, a manual on the obligations that buyers of gray market cars must meet.

Kokal explained to me that AICA wanted to keep imports alive, but the conversion process should be standardized. No more backyard engineers haphazardly putting things together. He also explained that many official dealerships wanted to keep imports going, too. When those dealerships ran out of their official allotment of cars to sell, they would import their own cars, convert them, then sell them.

This is echoed by some of the reports of the era, including in the Washington Post:

White and Peter Lissiuk, president of Emerald City Design in Gaithersburg, a converter, both speak of being approached by local authorized dealers who want either to buy their converted cars wholesale or have them convert cars the dealers buy themselves in Germany.

AICA also conducted its own research. A 1985 NHTSA report of safety complaints provided to AICA showed that none of the complaints were related to gray market vehicles. It also reviewed 1983 and 1984 DOT records and found no safety-related problems from gray market cars.

Sadly, AICA’s efforts didn’t stop the automakers from succeeding. As we all know, the Imported Vehicle Safety Compliance Act of 1988 was passed, cratering the importation of gray market vehicles.

The Aftermath

Decades later, the 25-year rule remains in place, and there’s no sign it’s ever going anywhere.

The process to get a non-conforming vehicle legal is different, too. Importers and converters must now go through a lengthy and expensive process just to get a vehicle onto the list of vehicles allowed to be imported before they hit 25 years old. Gone is the idea of cobbling together a car in your garage then sending in some papers.

Earlier, I mentioned how some official dealerships were concerned about liability suits arising from gray market imports. In 1992, the George Washington Journal of International Law and Economics explored whether U.S. Trademark holders should be held liable for gray market products.

In “Trademarks and Gray Market Goods: Why U.S. Trademark Holders Should Be Held Strictly Liable for Defective Gray Market Imports,” the journal explains that a person injured by a defective gray market product may desire to sue. In the event that they cannot sue the retailer they purchased it from or the manufacturer overseas, they may sue the manufacturer’s U.S. division even if the company never authorized the importation or sale of the good in the States.

The journal looked at previous cases where companies were found liable for injuries caused by products with their names on them, but produced in other countries. Of course, the best way to make sure that never happens is to stop gray market imports. The journal noted that the Imported Vehicle Safety Compliance Act was a major victory in this regard.

The 25 year import rule remains infamous today for halting the dreams of enthusiasts before they can even get off of the ground.

Money was certainly a factor, but they were not without other concerns about poor quality conformity conversions being done that could have put drivers in danger. Nobody wants to learn that a car they were told had airbags actually didn’t. Of course, the automakers complained about poor conversions harming their image.

Reputable importers had a solution that could have fixed this. Sadly, it was ultimately ignored.

As a final question for Dan Kokal, I asked him if he has any advice for car enthusiasts and younger importers. He told me that what shipping companies say is not necessarily correct. You can ship a vehicle younger than 25 years old and you may even be able to import it without modifying it. But you have to make sure you explore all of the options buried in import laws.