A jolt of adrenaline blitzed through my body when the hitchhiker I’d just picked up in the middle of Turkey began screaming at the top of his lungs. I flinched, turned toward the young man in the passenger’s seat, and was quickly relieved to find that he wasn’t screaming; he was singing. And before you knew it, I was, too, as things became supremely but pleasantly weird in my diesel, manual 1994 Chrysler minivan.

Last summer, I bought a broken 250,000 mile Chrysler Voyager minivan sight unseen in Germany, flew in from Michigan, wrenched for over a month to limp the machine through Deutschland’s strict TÜV inspection, and began testing the vehicle’s mettle (and my wrenching skills) via long road trips around Europe. This summer, I put the van through its hardest ordeal yet: A 3,500 mile round-trip to Turkey in the dead of summer.

I described last week the Driving Hell that I endured on what should have been a 20 hour trek from Germany to Turkey, but what ended up lasting closer to 30 thanks to grueling border checkpoints. The good news was that I arrived punctually to my friend’s wedding in Istanbul, and had a great time eating delicious food, talking with wonderful people, and doing variations of the Stanky Leg to music whose lyrics I couldn’t understand.

I Guess I’m Driving Deeper Into Turkey Than I Expected To

Though I’d set out solely to attend my friend’s wedding and to see a bit of Istanbul, my trek wouldn’t end there. “Hey man, so we’re all traveling to various places in Turkey starting tomorrow if you wanna come,” the groom, David, told me during his wedding. “Yeah, [my wife] and I figure we’ll have plenty of opportunity to travel together, so why not have a friends-honeymoon kind of thing?” he continued. “We’re heading to Cappadocia tomorrow.”

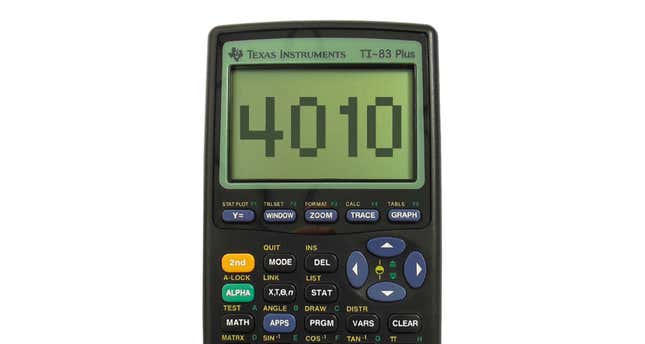

I knew nothing about Cappadocia, but every time I inserted the information David had just proposed into the pulsing Ti-83+ in my skull, the answer appearing on my frontal lobe’s remaining pixels always came out the same:

YOLO.

Realizing that I’d be a fool to ignore logic that sound, I checked out of my hotel; had a short conversation with the valet staff about my diesel, manual minivan (they seemed to legitimately dig the thing); and then began an eight hour trip east, in the opposite direction of Germany (which I’ll remind you, was already 30 hours away).

On the way out of Istanbul, I spotted a car club made up largely of classic American iron. I stopped, briefly chatted with a Mustang owner about his 1965 convertible (I myself drive a 1966), and then headed toward the highway.

The terrain on the Asian side of Turkey varied from large, yellow plains to rocky, jagged hills to dense woods. It reminded me a bit of New Mexico or Colorado.

The steep, hot grades were too much for some vehicles, and while seeing the disabled machines on the roadside frightened me a bit, my 250,000-mile 1994 Chrysler Voyager’s Italian-built 2.5-liter turbodiesel didn’t shudder at all. (Well, not any more than it normally does).

Four hundred and fifty miles later, I arrived in Göreme, a picturesque, ancient town built into beautiful rock formations.

Hot Air Ballooning In Cappadocia

I drove through unbelievably tight and steep streets, and checked into my “cave hotel”:

I quickly showered, dressed, and met my friends at their hotel restaurant, where I had an amazing Testi Kebab — a perfect culinary creation made of lamb, onions, garlic, peppers, and tomato, and cooked/served from a ceramic pot:

After supper, I walked to my hotel and basically died on my bed, resting away the struggle of sitting in an air condition-less van for over eight hours.

But my death was short-lived, for the bride and groom had arranged for a hot air balloon ride the following morning, with a meeting time before 4 A.M.

We arrived a few miles outside of Göreme on a tour bus, watched as operators filled balloons — strapped to the front bumpers of Land Rover Defender pickups — with hot gases via enormous propane burners. As the density of the gas inside the fabric enclosure decreased, the balloons assumed an upright position, and we —the bride, groom, their friends, and me — all filed into the basket.

Though I’m often afraid of heights, there was something about the balloon’s gracefulness — its smooth ascent and its steady sway devoid of harsh vibrations (also its high railings) — that made the experience the most tranquil flight of my life.

We all gazed out upon the beautiful landscape and watched the sun rise as the balloon drifted with the wind for roughly an hour, at which point the pilot pulled a rope, opened vents at the top of the balloon, and shot hot air out into the atmosphere. As the air ship dropped, all of us occupants in the basket crouched down into landing position, grabbed the loops of rope found on the inside basket walls, and landed as a man on the ground yanked the top of the balloon with all his might:

For the rest of the day, I joined David, his now-wife Duygu, and their friends touring the Cappadocia region. We got a tour of dozens of Christian cave-churches carved into rock formations:

We saw a ceramist form incredible shapes with clay:

And we visited an underground city that featured a fascinating ventilation system:

Hot air balloon propane burners awoke me early the following morning. I walked out of my hotel and saw enormous tear-drop shaped hot-air vessels dotting the sky.

The Groom Drives The Van Through Ridiculously Tight Streets

Look at the photo above, and you’ll see how densely-packed the city of Göreme is, and how much elevation change exists within city limits. It’s almost hard to believe that there’s space for streets between the buildings, but there is — and they are unbelievably hard to navigate, even in a relatively compact minivan like mine.

David, the groom (whom I’d met in a Detroit elevator years ago using the pickup line “Hey, so is that your Evo out front?” —it was his Evo, and the rest is history), wanted to drive my van to see what all the fuss was about.

He and I had a great time cruising around Göreme, with David surprised by the van’s torque and excellent five-speed shifter.

He stalled once, and nearly bumped the front of the van against a city wall trying to reverse uphill for a three-point maneuver after underestimating how tight one of the turns was. (He ended up employing the park brake to hold the van, then powering through the brake to avoid ramming the van’s nose against the rock wall).

David had a good time in Project Krassler, and so did his friend Jared, who took me to a museum before I left the group to head back to Istanbul.

Meet Adem, The Hitchhiker

On the side of the highway just outside of Göreme, I noticed a man standing on the side of the road with his thumb out. It was a young hitchhiker dressed in stereotypical backpacker’s gear: a huge pack, a foam roll, and a sleeping bag organized neatly in a vertical stack on his back.

I steered my van onto the shoulder and applied the brakes, downshifting into third, then second, then first. I pulled the shifter down, to the right, and down again into reverse, and backed toward the hitchhiker.

The young hitchhiker threw his backpack in through the side door, and sat up front. He introduced himself, and — using a translate app on his phone — communicated to me that he was a nurse who had just graduated school, and who decided he’d now “take a walk.” I congratulated him, and told him I was vlogging some of my trip; he said he was doing the same, and was down to be on camera.

A few miles down the road came the singing. It was alarming at first, because I didn’t know what was going on. But in time, I enjoyed Adem’s pipes, and I appreciated the guitar player’s confidence to just start singing in the passenger’s seat of a random person’s car. It’s bold.

Following Adem’s impressive performance, it somehow became my turn to sing. Since I have no singing skill whatsoever, and since I’ve made a name for myself on the mean streets of Troy, Michigan as the skilled rapper “I-Earn-Oxide,” it was time to drop some bars.

Adem seemed to dig my rendition of Eminem’s Lose Yourself, giving me a round of applause (out of pity, if we’re being real), and then introducing me to Turkish Eminem. It was incredible.

Here I was vibin’ to Turkish rap with a guy I’d never met, headed to a town I’d never even heard of (Aksaray), probably getting 33 MPG all the while in the greatest minivan of all time. It was glorious.

After listening to Turkish Eminem, Adem decided to outdo me with his own rapping skills, dropping some of the quickest bars I’ve heard since Ludacris’ part in Usher’s song Yeah. It was impressive.

I took a bit of a detour from my direct route to Istanbul to drop Adem off in Aksaray, where we both enjoyed Iskander döner — sliced grilled lamb atop bits of pita bread, all covered in tomato sauce and served with yogurt and melted butter. It was magnificent:

Adem and I parted ways in Aksaray, though we keep in touch on Instagram. I asked him about the recent fires in Turkey, and he responded with: “Hello David, we’re fine, but everything is on fire and it can’t be contained. The most beautiful places and forests of my country and the city I live in were burned. unfortunately i’m so sorry.”

It’s tragic, though I’m glad to hear that Adem is doing okay.

I’d never picked up a hitchhiker before, and I understood that giving a ride to a random person in the middle of nowhere, Turkey, where I have very few contacts was a questionable move. But over the past year or so, I’ve been thinking a lot about the concept of trust — about some of the incredible people who have put their trust in me over the years, about the relationships I’ve built as a result of putting trust in others, and also of the excruciating pain I’ve felt when trust is broken.

I initially wrote five paragraphs on the interplay between these potential results of giving and receiving trust, and on why, in the end, I’ve concluded that trusting people is worth dealing with the odd betrayal. I deleted those words because they seem a bit deep for a blog about a diesel manual minivan, but suffice it to say: I’ve resolved to err on the side of trust, and to factor in an occasional breach as just an unfortunate and inevitable part of life. The upside of giving trust is just too high to ignore, and I’m convinced that, so long as I’m smart about the way I trust, I should manage to avoid ending up modularized in a duffle bag in some back alley dumpster.

In this case, I saw that the hitchhiker was not physically intimidating, and his garb indicated to me that he was on a big trek that likely wasn’t going to end with him evading police behind the wheel of a stolen minivan. Obviously, I couldn’t be certain about this, but I decided I’d put my new, more pro-trust stance to the test.

It worked out beautifully.