I was in a great mood all of last week because of what I experienced in a 2021 Ford Bronco. I, someone who’s been obsessed with Jeeps since, basically birth, fell in love with Ford’s hard-core off-road SUV, and trust me when I say that you would have too if you’d done what I did. Let me show you.

An epic off-road race called King of the Hammers took place last week in California, and — keen to make its presence known in the off-road scene as it ramps up production of new rough-and-tumble machines like the Bronco, Bronco sport, Raptor, Tremor lineup, Timberline lineup, and more — The Blue Oval not only fielded three successful teams in the Ultra4 4600 stock class at King of the Hammers, but it also had a big presence in Hammertown, a gargantuan makeshift city in the middle of the desert.

[Full disclosure: Ford flew me to LA, had a Bronco waiting for me at the airport parking lot, fed me food, and housed me in a Palm Springs hotel whose nightly rate is likely higher than the value of most of my Jeeps. Combined.]

And I do mean “middle.” For miles in every direction, there are shrubs, rocky hills, lots of sand, more shrubs, more hills, more sand, then again a shrub that looked the same as the last one, then some more hills that looked like the ones before. It’s clear that, at least in this part of the country, The Grand Creator got bored and used the control-C, control-V buttons.

Why was I out there? Well, Ford invited me, presumably because it wanted me to communicate to you that the company is a real player in the off-road scene. But I didn’t accept the invite to see the race and to tout Ford’s investment in one of the world’s premier off-road events. I was out there for one simple reason: I wanted to drive the crap out of some Broncos in the desert.

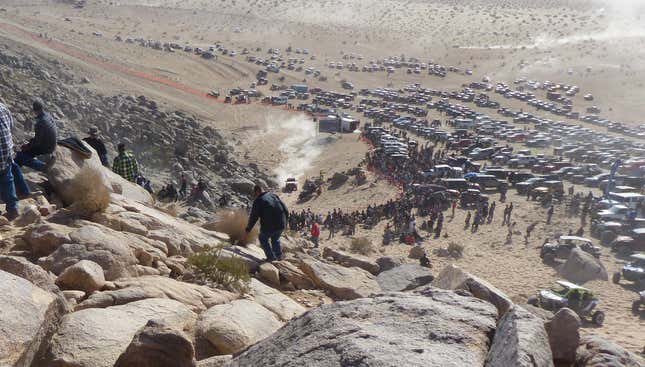

Before I get to that, I’ll just say that the race itself was epic. Thousands of people gathered from all around the country to see absurdly-capable off-road specialty machines blast through terrain that seems almost impassable to navigate by vehicle.

Just look at all of the dust and the massive boulders that somehow constitute the race track — the whole thing seems impassible, and yet it isn’t:

Here are some photos of the Broncos in the race:

I even had a chance to look at one of Ford’s race vehicles up close:

Behold these badass, ground clearance-improving portal axles:

You can see the lower control arm in the photo above. Here’s the upper with its rather interesting joint:

Check out this Dynatrac ProRock XD60 solid rear axle (worth noting: the front diff is the factory Dana AdvanTEK unit with electric locker):

As you can see, damper cooling is a big deal.

You can see the tall finned coolers for the front dampers under-hood:

Anyway, as badass as the event was, I’ve personally never really been too much into professional racing, as my favorite aspect of car culture is its inclusivity (edit: which is why I wasn’t a big fan of the political stuff at the event, if I’m honest). And let’s be real, race vehicles like these cost a ridiculous amount to build, and aren’t really accessible to the masses.

What don’t cost a ridiculous amount, though, are the vehicles on which these race trucks are built (relatively speaking). These are cars that hundreds of thousands of people can buy and relate to, which is why when Ford gave me the keys to a Ford Bronco Badlands two-door with a seven-speed manual and said I could do whatever the hell I wanted for a few days, I ditched the race and headed out into the desert.

Hitting The Desert In The Ford Bronco

I’ve driven the Ford Bronco before — at the vehicle’s launch program last year in Texas. That event included a good amount of rock crawling, river fording, and hill climbing, but little high-speed off-road driving. Though my review was largely favorable, it became clear during my two days in Johnson Valley, California about a week ago that the Bronco is somehow even better than I had first noticed. Honestly, I’m awe-struck by how perfectly Ford executed its Jeep Wrangler competitor by actually not competing for the top spot in certain areas.

Way back in 2017 shortly after Ford announced the return of the Bronco, lots of speculation about the vehicle’s front suspension abounded, with Automotive News even claiming that a solid front axle was on its way. I responded to that story with skepticism, writing this in my article “I Don’t Believe For A Second The New Ford Bronco And Ranger Will Get Solid Front Axles:”

I’d absolutely love for Automotive News to call me up one day and tell me to eat my sock, because Ford had confirmed a solid beam-style front axle. I want the durability, articulation, simplicity, and the aftermarket support. I want the Easter Jeep Safari to be more than just jacked-up JK Wranglers. All that, to me, is worth enduring the taste of cotton drenched in my own foot-sweat.

I’d like to take back every word of that paragraph. Not because my willingness to consume a sweat-soaked sock has waned over the past five years, but because I’m actually glad Ford chose independent suspension for the Bronco. Really, really glad.

By foregoing a solid axle, Ford gave up a bit of rock-crawling capability while gaining a ton of high-speed desert-running skill. The Blue Oval gave up the top spot in rock crawling (where the Bronco still does quite well) in order to dominate the desert running (where the Wrangler doesn’t perform so well). Obviously, there were some reasons beyond “Why be equal or slightly better than the Wrangler at rock crawling when we can be a little worse at that but much, much better at high-speed off-roading.” The basic platform on which the Bronco is built — shared with other vehicles like the Ranger and Everest — lends itself to independent suspension, so you can bet that saving money by using a common suspension architecture played into the IFS decision.

But even if the dollars and cents weren’t a factor and the Bronco had been a clean-sheet design, I think IFS would still have been the right move. As I learned a week ago, the machine is a beast in the three most critical areas of desert-driving — high-speed running on lake beds and washboard roads, hill and dune climbing, and donut-ripping.

High Speed Desert-Running

As soon as I arrived at the dirt road headed to Hammertown (which, again, isn’t an actual town, just an enormous gathering of RVs, trailers, and off-road machines in the middle of the desert), I found myself surrounded by total madness. People blasted through the sand in ATVs and built-up 4x4s, some using the main road, many just veering off and gassing it past everyone, catching air as they hit sand “whoops.”

“Lets Go Brandon” flags waved, chants of “Fuck Joe Biden” seemed to erupt out of nowhere, camo garb abounded, but above all, 4x4 culture flourished. There were lifted XJs and ZJs, and old Broncos and 4Runners and Explorers, and every pickup truck you could ever imagine — even Rivian made an appearance. This wild, gasoline fume-filled area in Johnson Valley was, for about a week, the off-road Mecca of the world.

Right away, as I drove down that road leading into Hammertown, I could feel that the Bronco was at home. The machine’s capabilities were well beyond what I was used to from my fleet of solid-axle Jeeps. My two-door manual Badlands model wanted to be pushed harder over even higher amplitude undulations. I obliged.

If I had the courage, I pressed the accelerator pedal and let that 300 horsepower 2.3-liter turbocharged inline-four jump the truck from peak to peak of each little mound in the path ahead, smoothing out the ride. But when I didn’t have the courage, and the front end fell deep into troughs, rose up, jumped over a hill, and landed inside another trough, the Bronco remained unbothered. Sure, the front end was bucking like, well, you know, and when the front dampers reached the end of their stroke, the vehicle delivered a squeak as it hit its jounce bumpers, but even that felt remarkably controlled.

Just point the Bronco out toward the desert, press the gas pedal, and go. The thing will handle it. The approach angle is so good that even if you go nose-first into a trough, everything will be just fine. The damping is so good that, even when, outwardly, it might look like the SUV is hopping up and down over bumps, inside the cabin it’s hard not to wonder how the ride isn’t harsher. I gave my colleague Clay, a former engineer from Chrysler, a ride, and he was just as impressed.

“The way it handled the bumps and the whoops, absolutely incredible. For a stock vehicle, that’s just insane...doing it for hours, it just keeps going and going and going and wanting more.”

He and I expected the two-door to ride poorly, since the short wheelbase leads to bigger changes in pitch for a given bump when compared to the four-door (or the Raptor, which did handle the whoops a bit better), but actually, it wasn’t bad. The Bronco is a desert-running beast.

Hill/Dune Climbs

Another critical characteristic of a desert runner is its ability to confidently climb loose grades. Johnson Valley was filled with steep gravely hills and sand dunes — some of the most treacherous terrain you can put a vehicle through.

As I’ve mentioned far too many times here at Jalopnik, I was on the powertrain cooling system for the Jeep Wrangler JL. Based on that experience, I can tell you that sand is among the most thermally taxing environments in existence. If you’ve ever taken a vehicle to dunes, you’ll understand why.

Dune climbing is a hellacious combination of incredibly high engine loads (to get up some inclines, you have to press the accelerator pedal to the floor for minutes at a time), high engine speeds (to keep wheel speed up and to get the power you need to climb the grade), little airflow (the vehicle is barely moving despite your engine revving to the sky), often high ambient temperatures (and high ground temps, too), and tons of churning in drivetrain gearboxes (which means heat generation).

Seriously, dune climbing can be like towing up Davis Dam with no ram air and loads of wheel-spin. It’s hell on an automobile.

I don’t know how the Bronco would do climbing grades for hours at 110 degrees, but what I can tell you is that in about 60 degree weather, the thing climbs like a goat. The image above shows a treacherous grade; the photo doesn’t accurately show how steep the thing is; trust me, it’s no joke.

I began with the satisfyingly-notchy shifter in first, figuring I’d accelerate into second in four-wheel drive high, and hold second all the way up the grade. This didn’t work. At all:

Hundreds of off-road enthusiasts watched as a vehicle that many of them have been curious about — the new Ford Bronco — roared halfway up the hill, bogged down in the deep sand, and then shut off. (The Bronco’s stall recovery feature fired the engine back up when I pressed the clutch; this was quite... clutch out in the dunes).

After five or six embarrassing attempts, I regrouped. First, my tires were at 35 PSI; this was too high, so I aired down to 20. Then one of Ford’s engineers gave me a tip: Try low range, third gear.

I had tried low range, but only got to second gear. I wasn’t able to get wheel speed up high enough, so the Bronco bogged down in the sand. My other attempts were in high-range, where the vehicle didn’t offer the right combination of torque and wheel speed. I also only had the rear locker on.

So, with tires aired down, I locked both differentials, started in second gear, gassed it towards the grade, shifted into third just before the hill, and began ascending. The engine began to bog down, so I stepped on it. For a moment, the engine slowed, and I was worried I’d once again be backing down the hill.

But just a moment later, the engine came alive. Boost kicked in, and the Bronco climbed up the hill easily. Low range, third gear was the sweet spot for all hill climbs during my time in Johnson Valley.

The little four-cylinder is a great engine because it happily revs to the sky, so the vehicle doesn’t feel like it’s about to explode when I keep my foot on the gas as the motor bounces off the rev limiter (this is the case for most modern engines; older engines like the Jeep 4.0 under the hood of so many off-roaders is not happy revving above 4,000).

Power delivery is something I had to get used to, as throughout the weekend, whether I was in low range climbing grades or in high range just going through deep sand, I had to be careful not only to choose the right gear, but to be quick on shoving the pedal to the floor. There were times when I’d upshift, the Bronco would slow down, and it would feel like the vehicle was about to stall out. But then the surge of torque would hit, and the thing would enter beast-mode.

It took some time getting used to choosing the right gear, knowing when to be in low and high range, and getting a feel for the 2.3-liter turbocharged engine’s power delivery, but once I figured that all out, climbing grades — especially with the lockers on — became a genuine joy.

And that clear front camera helped me crest those hills without worry that there was a sheer cliff or another vehicle on the other side.

Donuts

We’ve got to talk about donuts, because there are few things in the automotive world as fun as spinning a $50,000 vehicle in circles for absolutely no reason.

The Bronco, with rear diff locked, can rip some tight ones. I used a 330 horsepower 2.7-liter V6-equipped four-door model to create rings on the desert floor, and my god was it easy. The motor ripped the rear tires loose, and gave me a near-instant 360 degree view of a dry lakebed. It was epic.

Late Night Off-Roading

After a few days off-roading the Bronco in the desert, I found myself alone and tired. It was Saturday, and I had a noon flight the next day three hours away in Los Angeles. I figured I was going to have to get up at six. So at around 6 p.m., I left the madness that was Hammertown, and headed to my hotel in Palm Springs.

About 20 minutes outside of Hammertown, my friend Clay (the former Chrysler engineer I mentioned before) called me; we’d been trying to get in touch for a few days, but lack of cell service in the desert had made that difficult. The last thing I told him before we’d gotten cut off was “Dude, I’m in the coolest place you can possibly imagine.”

Clay’s sixth sense had, over the day or so since we’d last spoken, led him to somehow conclude that I was in California, so that’s how he opened up the conversation. “You’re in LA right now, right?”

“No. But close. I’m at King of the Hammers,” I responded. Clay, a big off-road fan, told me he had recently traveled from his home in Fort Worth to LA for some much-needed R&R as he’d recently moved on from his old job. “Dude, I’m coming. Be there in three hours,” he responded.

“Screech!” I hammered the Bronco’s brake pedal, and ripped a U-turn. My time at Hammertown wasn’t done. As for my early wake-up, I figured I could sleep when I’m dead.

If there’s one thing I’m most thankful for in this life, and in this career, it’s that I’ve been able to make some incredible friends through cars. Not just friends to hang out with, but friends whom I connect with on an almost spiritual level. Friends who live thousands of miles away, but who remain as loyal and as present in my life as anyone could ask for. Clay is one of those friends.

He and I met at Chrysler; we used to go on epic weekend road trips. We’d use an M-plate (a company vehicle) — we even checked out the Ram Long Hauler concept one weekend to head to Memphis — and head out of town on Friday after work. We’d drive as far as we could before we fell asleep in the car. Then we’d drive some more until we were as far away as possible, but not too far to where we couldn’t 1. eat some excellent food (we did a barbecue road trip to Kansas City once) and 2. get back by 8 A.M. Monday morning. Clay is the ultimate road-trip partner, and those trips created lifelong bonds.

Anyway, roughly three hours after our call, at about 10 p.m., Clay showed up to Hammertown, ditched his rental Dodge Charger in the desert, and the two of us beat the ever-living crap out of that two-door Ford Bronco Badlands.

Over that corrugated desert floor, the Bronco’s nose dove into troughs:

Then rocketed over whoops:

Then nose-dived into troughs again:

Then back again over the whoops:

Then it was back to the compression stroke for the front dampers:

It all looks so jarring from the outside, but from the inside, things were under control, and Clay and I couldn’t help but remain in awe of the Bronco’s skills.

Clay and I noticed dozens of vehicle headlights all pointing towards a hilltop covered with other vehicle headlights, almost like ants blindly headed to their colony. We followed the pack, and wound up at an obstacle called Chocolate Thunder, where thousands of people watched custom-built off-road rigs attempt to crawl an absurdly treacherous grade made up of humongous boulders.

Camp fires blazed, fireworks popped off, beer flowed from bottles, anti-Biden chants echoed, and strangers bonded over a shared passion for off-road culture as they cheered vehicles over the rocks.

For hours, incredible machines — many equipped with 40-inch tires, steel cages, locking diffs, and extremely expensive dampers, axles, and tires — climbed a steep rocky valley flanked on both sides by spectators huddling next to fires.

One vehicle even flipped shortly after some passengers had stood on the back seats, unbuckled. Thank goodness those folks had hopped out prior to the run, though I wouldn’t have been surprised if they hadn’t; it seemed that the whole event was pure lawlessness. Maybe a bit dangerous lawlessness, but definitely glorious.

I don’t want anyone reading this to think the Ford Bronco is perfect. Fuel economy isn’t great at 20 MPG combined, the parking brake location on the lower dash by your left knee still sucks, wind noise is prominent compared to most vehicles, and the on-road ride isn’t great. But if I’m honest, I’m only mentioning these things to give this otherwise-glowing article some balance. I have to consciously do this because, as an off-road enthusiast, I was blown away by what that red two-door Badlands with a stick shift can do out in the desert, especially given what it can do on the rocks. It may be the most well-rounded off-road vehicle I’ve ever driven.