Buying a car is pretty exciting for any car enthusiast, especially if the vehicle you’re buying is one you’ve wanted for a long time. I know that’s true because, over the past week or so, I’ve been engaged in purchasing a car that I’ve wanted for almost my entire life: a Porsche 911.

Now, being an automotive journalist without well-to-do parents, my prospective 911 isn’t my first choice for generation or model. But it’s what I can afford (especially with 911 prices going crazy still), and truth be told, it offers the full 911 experience with very little compromise. I’m talking, of course, about the 996 generation, which spanned model year 1999 to 2005.

Now, before you keyboard warriors start losing your collective shit over rear main seals, intermediate shaft seals and fried egg headlights, I’ll say that, as someone who worked with (specifically in parts) Porsches for years, I’m well aware of the potential hazards of buying a 996. That’s why this article is about helping someone dodge the bullet of buying a bad one.

996 Porsche 911: The Hunt

The first step in finding a good 996 (or any good used car) is actually finding it. That seems obvious, but with the wide variety of online listings, forums and car club pages, there are way more places to look than there used to be. To simplify things, I use AutoTempest to hit around 90 percent of the major listing sites. I also like to check forums like Pelican Parts and Rennlist because often, cars listed there don’t go up on sites like Craigslist, and they’re enthusiast-owned, which can be good.

Now that you know where to look, you need to know what to look for. Using the 996 as an example, you have a few different variants to pick from based on your budget. I wanted a rear-wheel drive car with a manual transmission. I’m also not too fond of convertibles and wanted to avoid non-black interior colors.

That narrows the field down a ton, but there are still more criteria to consider. With the 996, you need to decide if you want a first-generation or second-generation car. An early (1999 and 2000) first-generation 996 came with no driver aids other than ABS; it had a cable-actuated throttle rather than drive-by-wire, and a more robust dual-row IMS bearing which is the least failure-prone of all the designs. 2001 and 2002 models got an electronic throttle and the least stout IMS bearing.

Later second-generation cars (2002-2004) came with a larger, more powerful 3.6-liter engine, slightly revised styling, a glovebox, better quality interior materials and clear headlights. They also sport a revised, slightly less failure-prone single-row IMS bearing and an electronic throttle.

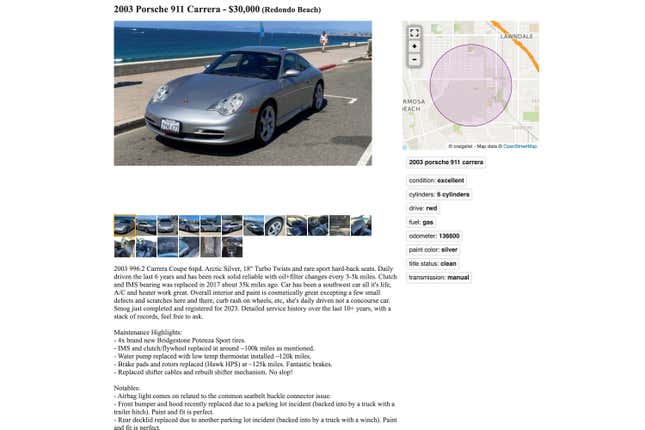

I honestly didn’t have a major preference between first and second-generation 996s, so knowing all that, I found a very promising looking 2003 Carrera in Arctic Silver over black with a six-speed manual and a boatload of service history for a not-insane price. This leads us to…

The Test Drive

My prospective car was listed on Craigslist, and the ad offered plenty of information, halfway decent photos and what seemed like a fairly honest representation of the car. Of course, anyone who has tried to buy a used car online knows that things can be deceiving.

My first step was reaching out to the seller, Jon, who immediately came off as an enthusiast. We settled on a time to meet so I could check out the car and drive it, and not only did he show up on time, he brought the car in its natural state: clean, but clearly being used regularly, and the engine compartment hadn’t been cleaned up or detailed.

After shaking hands and bullshitting about cars for a few minutes, I began visually inspecting the 911. This is important because keeping your eyes open and knowing what to look for can save you a ton of time and money before getting further into the buying process.

The car presented well and looked much the same as it did in the Craigslist listing. The body was in overall good condition, with some previous parking lot damage (since repaired) that had been noted in the ad and pointed out by Jon in person. A 911 is a low car, so peeking underneath is tough, but there were no obvious drips or smells of burning oil or coolant. I opened the decklid and the frunk and, again, no surprises. For a car with 136,000 miles, it seemed in good shape.

The test drive offered more of the same. While I didn’t get to see a cold start because we met at a neutral location near Jon’s work, the car felt like a 911 should. The steering was direct, the brakes were strong and the engine pulled well and sounded great. The gearbox felt good too. The air conditioning worked, and the interior felt well cared for, if typical 996 cheap.

After the test drive, I went home and collected my thoughts. I wrote down some notes about the drive, the visual condition of the car and the vibe I got from Jon. This is an important and overlooked step, especially if you go and look at a lot of vehicles and have to keep track of all those experiences.

I checked out a couple of other cars but decided that Jon’s silver 2003 was the right one for me, which led to…

The Inspection

One of the most important things you can do when buying a European car out of warranty is to organize a pre-purchase inspection, or PPI. (This applies to other vehicles too, but it’s especially important with German cars of this era.) This involves you taking the car to a shop or a dealer and having them professionally inspect the vehicle to give you a clear picture of your potential purchase’s condition. People skip these because they cost money, but — and I say this from very expensive personal experience — please don’t.

Asking the seller if they’re amenable to having a professional inspection done is an important test in and of itself. If they’re enthusiastic about it, then it’s likely the car is being represented fairly, and they have nothing to hide. If they don’t agree to submit the car to a professional inspection, walk away.

Luckily, Jon was cool with me having the 911 looked over, so I arranged a PPI with a well-regarded Porsche shop on LA’s west side to make the drop-off and pick-up convenient for him.

We’re lucky in LA to have a huge variety of quality Porsche independent shops, and in the end, I went with one that I had some experience with (I’d worked with the shop previously) and which could fit me into their schedule. That shop is called Auto Werkstatt, and I’d recommend them to anyone with an air- or water-cooled Porsche in LA.

Auto Werkstatt was kind enough to let me come and oversee the PPI process, and document it for this story. They’re a great shop run by enthusiasts that services most German marques, and if you’re in the area, they deserve your business.

The thing about a PPI on a 911 that might throw a lot of people is the cost. Auto Werkstatt charged me around $630 for the service. That sounds like a lot, and it is, considering they don’t fix anything during the inspection, but a really thorough examination takes time (around three hours) and time costs money.

My mechanic, August, started the PPI with a visual inspection. Unlike my educated-but-still-amateur eye, he’s a pro with almost two decades of experience. He also has a lift, which means he can see things I couldn’t in a Lowes parking lot, like the fact that the nuts on the swaybar end links aren’t original. Is it asinine to point something like this out? Yes. But this is the kind of thing you want your PPI mechanic to notice.

As the internet will tell you repeatedly, the big thing to look for on a 996 (or 986 Boxster) is an oil leak at the joint between the transmission and engine case. This typically means either a rear main seal leak or a leak from the intermediate shaft bearing cover. Neither is good, and fixing either means removing the transmission. Luckily, this car was completely bone dry underneath. Score!

The big pitfall avoided, we proceeded with the inspection and did find a couple of issues. It’s a 19-year-old sports car with 136,000 miles, after all. The big one is an air-oil separator that’s past its prime, which isn’t mega urgent, but it’s a $2,000 job to fix if you take it to a shop. Parts alone are almost $600. Next, one of the rear shocks is leaking, and all four could use replacing. I want to put coilovers on the car, though, so while this is a bummer, it’s ultimately not a big deal. Lastly, as we moved towards the interior, August discovered the early warning sign of a failing window regulator. This one is a fairly easy DIY with the regulator costing under $200, so again, not a big deal.

Not bad, right? So, with that out of the way, August took the car for a brief test drive. The car had sat overnight, so we got to see a good cold start, thankfully with no big plumes of smoke or anything otherwise untoward. The test drive proved uneventful, and August confirmed my sentiments on the overall driving experience. It’s solid.

The last part of the PPI is something you, as a home gamer, aren’t able to do, no matter how skilled. It involves hooking up a Porsche dealership computer, aka PIWIS, to the car to see how it’s been driven, and check for any stored trouble codes.

By “how the car has been driven,” I mean how much time the car has spent at or around redline, and even how much time it’s spent over the indicated redline. I don’t know if this kind of electronic tattle-tale is unique to Porsche, but it can indicate how hard a car has been driven. This car only saw 11 ignitions over 7,900 rpm and didn’t suffer, which is good. But the engine did show 18,202 ignitions between 7,300 and 7,900 rpm, which August explained is a lot.

That sounds insane, and it kind of is, but this is a car that’s meant to be driven hard. Given the overall mechanical condition of the car, high-rpm driving isn’t the end of the world. It might put off some buyers, which would be understandable, but I want a car that’s been well-used and cared for since I plan on driving the hell out of it anyway.

In the end, August gave the car a thumbs-up, even going so far as to mention that the thorough inspection generated one of the shortest post-PPI lists he’s seen. This is a big win, and it means that I’ve found a good example and one worth buying. Which I did, for less than $30,000.

A Final Word About Porsche IMS Bearings

So, as I mentioned previously, if you talk about 996-generation 911s or 986-generation Boxsters, you’re going to get a bunch of people warning you about the perils of the IMS bearing, and its ability to take out an entire engine if it fails. The issue has been widely publicized, and many people have made a lot of money off the sale of replacement bearings and their installation.

Here’s the thing, though: it’s not that big of a deal. The failure rates are a lot lower than you might think. Just breathe. Everything is fine. Nothing is fucked here, dude.

The IMS is such a hot topic because it’s a small, ticking-clock kind of problem that can turn into a massively expensive engine rebuild. It’s something you can’t easily see or definitively test. It’s easy to fearmonger people into spending $3,000 to replace the bearing preventively (and the clutch while you’re in there, if it’s a manual car).

Porsche claimed the failure rates on the early dual-row IMS bearing cars are between one and three percent. That’s tiny. Even the most failure-prone version, the narrow single-row-bearing 2001 and 2002 cars, have a claimed failure rate under 10 percent. That’s not nothing, of course, but now that we’re 20 years on, most of the cars that were going to have a failure have likely had one already.

So, the moral of this story is that you shouldn’t be scared away from a brilliant, affordable sports car just because of a serious but over-reported problem. If a car you’re looking at has had the bearing replaced with an aftermarket solution, that’s awesome, but those cars will have a price premium associated with them. If it hasn’t had the bearing done, chill. Look at your oil filter during services (which you should be doing regularly) to check for metal particles. If you’re extra proactive, send your oil out for analysis by a place like Blackstone Labs and buy a magnetic drain plug because the bearing material is ferrous and will collect on the magnet.

If you need to do a clutch change or have a big rear main seal leak or IMS cover leak, you should replace the bearing while you’re in there. It’d be dumb not to. But there’s no reason to spend a bunch of money if you don’t have a specific reason. Just enjoy your car the way it was meant to be enjoyed. That’s what I’ll be doing with my freshly-PPIed 996.