One day last December, Tanisha Coley visited a Kia dealership in Stamford, Connecticut and filled out a computer-based credit application to figure out what kind of car she could afford. Soon after, she left without buying a vehicle, but ended up more than $17,000 in debt anyway.

Weeks later, Coley discovered something alarming had been registered on her credit report: an auto loan, opened on Dec. 12, 2016 at the dealer, for a 2013 Mazda. The loan had a total balance of $17,737, the report said.

But Coley was nowhere near the dealer that day, her attorney, Joanne Faulkner, said. “The dealer actually called her that day and said, ‘We’re still trying to get you this car,’” Faulkner told Jalopnik.

The Kia dealer, according to a lawsuit Coley later filed, “had electronically booked the car loan for Ms. Coley with Credit Acceptance Corp. for a 2013 Mazda that she never purchased or took possession of.”

The car was a ghost. Coley, a mother of five, had a roughly $18,000 loan to her name for a car she never even owned, for a loan she never laid eyes on.

When Faulkner intervened, Credit Acceptance returned the contract to the dealer, she said. But the incident—first highlighted earlier this year by a Forbes contributor—left a significant mark on Coley.

“She was very upset, obviously,” Faulkner said. “When it goes on your credit report and you find out that you own a car that you didn’t own. And, of course, during the time it was on her credit report, she couldn’t get credit for another car because everybody thought she already had one.”

The case was eventually settled, Faulkner said, but it represents the risks that can arise from automakers that take part in the increasingly common practice of using electronic loan contracts.

“It’s pretty risky for anybody to use an e-signing contract, because I don’t know what safeguards there are,” Faulkner said. (Kia declined to comment.)

The case of Michael Criscione presents more problems that can arise from e-contracts, attorneys and consumer advocates say.

One day in March of 2016, Criscione was looking for a new vehicle when he came across a used Ford F-250 listed for roughly $19,000 at Atlantic Motors, a used auto dealer in Westbury, Connecticut. After inspecting the pickup in person, he negotiated a sale price of $18,000 and bought the truck without ever signing a loan contract.

Criscione had provided credit information to a salesman, and even what he believed was a bill of sale. But he’s adamant that he never laid eyes on an electronic loan contract that Atlantic claims he signed.

That’s because Atlantic—using a forged signature—had enacted the contract without his knowledge, according to a lawsuit later filed by Criscione against the dealer in federal court.

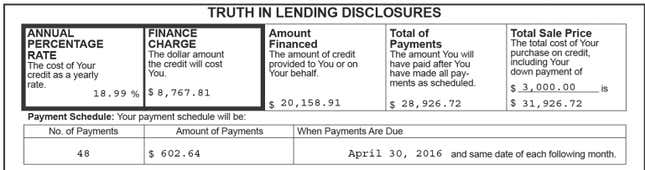

The contract, the suit says, didn’t include the $4,000 trade-in that Bob agreed to for Criscione’s 2001 Chevrolet 2500 HD. It listed a cash sale price of $20,350—more than $2,300 than the price Criscione agreed to with Bob, in addition to a staggering interest rate of 18.99 percent.

“At no time did I enter into any retail installment contract for the vehicle,” Criscione said in an affidavit, “and Atlantic never provided me with a retail installment sales contract.”

E-contracts have been a fixture of American commerce for nearly 20 years. For tax returns or a trip to the grocery store, we’ve long considered it standard operating procedure to affix an electronic signature to complete a transaction.

That hasn’t been the case for auto dealers, who’ve slowly—and grudgingly—taken to adopting electronic contracts into their businesses. But as the auto industry moves toward a tech-heavy future, more auto dealers are buying into the idea of changing the paper-heavy way we’re accustomed to buying a car.

Unlike the age-old tradition of filling out a stack of paperwork, e-contracts present a more streamlined approach for a hypothetical tech-savvy car buyer. To proponents, e-contracts are a beacon of efficiency and convenience for dealers’ day-to-day operations. And, they say, it creates an environment that customers of today are more accustomed to, while making it a better experience for them to completely understand the intricacies of a deal.

On Thursday, in an indication of where this is leading, Toyota’s financial arm announced it had successfully processed the first remotely captured electronic customer signature on a finance contract, through a partnership with technology provider RouteOne. It opens the door toward dealerships selling a car completely online.

One company involved in making e-contracts more widespread is Dealertrack, which saw a 20 percent increase of auto dealers using its service between 2015 and 2016.

The company explains in a video tutorial that, once a credit application is approved, the e-contract process is a breeze. Background data of the consumer is entered into the Dealertrack program, and then submitted to lenders for verification.

“Once e-verified you can print a copy of the contract to review with your customer,” the video’s narrator says. The customer signs an electronic signature, which can then be affixed to the contract with a simple touch of the screen or a click of a mouse. (Dealertrack didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

The problem, according to consumer advocates and attorneys who spoke to Jalopnik, is that e-contracts make it easier for some auto dealers to scam consumers, or to stick them with terms they were not aware of.

Take the review process described by Dealertrack. Some dealers avoid printing out a copy altogether for the consumer to review, according to court documents and interviews with nine attorneys, consumer advocates and car buyers.

Without a hard copy of the loan agreement to review, they say, dealers have an easier time slipping in extra fees and add-ons that unwitting consumers never agreed to in the first place. And it’s harder to prove a customer didn’t sign a contract when it’s electronic—as one attorney put it, they render handwriting experts useless in court.

“It’s easier to sneak those things in when they’re looking briefly at a computer screen than when they’re looking at a piece of paper in front of them,” said Dan Blinn, an attorney who has represented clients with e-signature problems. There’s also the possibility that dealers can sign an electronic contracts “that has not been seen or agreed to by the consumer,” he said.

Court documents reviewed by Jalopnik reveal there are numerous examples to illustrate Blinn’s point. Some cases appear as egregious at Coley’s; others are more complicated to unpack. Dealers have been accused of manipulating trade-in values on old cars, entering higher purchase prices than were promised in person, including insurance the buyer never wanted.

Others have failed to provide copies of the loan contracts to review at any point in the process. All told, the scenarios leave consumers with extra fees and sometimes-burdensome loans that are destined for failure.

It’s an issue that’s difficult to quantify, but attorneys say there’s an increasing frequency of cases centered around auto dealer fraud with e-contracts. Blinn said nowadays about 20 percent of his prospective clients with auto loan issues have contracts that are enacted through an e-signature process.

Adam Taub, a Michigan-based attorney who deals with e-signature issues, has also witnessed a notable uptick in cases in the past couple of years. He said that electronic contracts help “further a system that was already functioning to cheat consumers.”

“This takes away any hope at all of subprime and low-income consumers making an informed decision about credit prior to being bound to the terms of credit,” he said.

For car buyers, understanding every nook and cranny of a loan document can be a complicated task. But in a typical transaction, there’s a set of boxes that cuts through the clatter and spells out the basics, and that’s because of the Truth In Lending Act.

Implemented in 1968, the law has a straightforward premise: when it comes to consumer credit, the terms and cost of obtaining it must be disclosed. For decades, the act was enforced by the Federal Reserve, the central bank of the U.S., under the ominous name of Regulation Z. (Today, it’s overseen by the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau.)

In the auto industry, the law’s effect is made abundantly clear on loan documents with the so-called Truth In Lending Disclosures. This shows everything from the annual percentage rate, the number of payments that need to be made, and how much each payment must be.

“You’re supposed to get the terms in a form, so if you actually wanted to, you can take them and shop around,” said Rosemary Shahan, president of the California-based Consumers for Auto Reliability and Safety.

Even with a paper contract in hand, consumers can still have a difficult time convincing auto dealers to turn over a contract that’d allow them to compare it with other shops. Occasionally, attorneys say, a salesperson will play games with a consumer and obfuscate the pertinent parts of a loan contract. But customers have every right to reach out and “grab that paper contract,” said David Valdez, a California attorney who represents clients in e-signature cases.

With an electronic contract, Valdez said, “a customer can’t even do that.”

“So that last line of defense of being able to pick up that contract and look at it is gone,” he said.

Arricka Scott ran into that issue in September. The 23-year-old was tired of relying on people for rides to her job at the University of Michigan hospital.

“The bus doesn’t even run where I stay at,” Scott told Jalopnik. “So yeah, I need a car.”

That month, she had a coworker take her out to a dealer in Metro Detroit to check out a 2014 Jeep Compass. Once she arrived at the dealership, U.S. Auto Sales, the salesman slow-walked the process and—according to Scott—refused to let her take the Compass for a test ride. Time ticked away, and the colleague who drove her needed to leave to catch her shift. Scott understood, but it left her in a serious predicament.

“I had to get that car,” she said, “or I would have been stuck.”

Panicked and visibly rushed, Scott started signing off whatever the salesperson placed in front of her. At no time was she given any paperwork or shown the Truth In Lending disclosures, she said.

“I got on the computer and he told me, ‘click here, click there, click there,’” she said. “I knew the [finance] company that I got the car with, that’s about it.” No paperwork was provided by the dealer, and she didn’t find out the loan amount until later, when she called the finance company, Credit Acceptance Corp.

“I would’ve gotten fired that day if I didn’t get the car,” she said. “They knew the situation. I was pressured into getting it.”

A few days later, the Compass was sidelined with transmission issues. The car was towed to her grandmother’s house, Scott said, “and it’s been there ever since.” She’s been driving a rental to get to work while she tries to sort out the situation.

In 2016, U.S. Auto Sales signed a probation agreement with the Michigan Secretary of State over alleged violations of a state law regulating motor vehicle repairs.

The agreement, obtained by Jalopnik, shows that U.S. Auto Sales was cited for “failure to reveal a material fact” and making “either orally or in writing an untrue or misleading statement of a material fact.” (Update: After publication, U.S. Auto Sales said by email its policy is that “all customers receive a copy of their paperwork whether e-signed or physically signed.”)

Just months after filing for bankruptcy, Scott’s worried about her credit getting ruined again. Credit Acceptance told her she owes $13,000 on the loan, but she’s put off payments while she considers filing a lawsuit. Scott said she wholly regrets not thinking through the situation more at the time.

“I was in a tough situation at the moment,” she said, adding: “I wasn’t in my right mind. I get paranoid when it gets around a certain time and I know I got to go work.”

Laws governing the use of electronic signatures date to the early 2000s, when the federal government passed the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act. But auto dealers have been slow to adopt electronic processes.

Those who have noticed a “number of efficiencies associated with it,” said Paul Metrey, vice president of regulatory affairs for the National Automobile Dealer’s Association. When dealers order inventory from automakers, Metrey explained, they finance the purchase through what’s known as a “floor plan” line of credit.

The moment a car’s sold to a customer, the dealer has a brief window—typically about 24-48 hours, he said—to pay off the floor plan line of credit that’s linked to the unit being sold. “It presents a real cash flow issue,” Metrey said.

Dealers with e-signature processes in place have found that, in a matter of hours, “they can get the funds necessary to pay down the floor plan line of credit,” he said. Beyond that, dealers feel it shrinks the time that’s needed with the consumer to complete a sale, and it helps detect errors much sooner, Metrey said, “so you can react more quickly to it.”

“The ones that’ve adopted it are certainly hopeful it’ll become more and more available,” Metrey told Jalopnik.

If this past year’s any indication, more auto dealers are indeed coming around to the idea. About 80 percent Nissan dealerships, for instance, use e-contracts today, Automotive News reported. Since 2013, RouteOne, a company that facilitates the use of e-contracting among lenders, has increased the number of dealerships on its network by 48 percent, according to the trade publication.

Some states have laws that’ve stymied the expansion—California, in particular. Before the federal e-sign law was passed, California enacted legislation that prohibited the use of electronic signatures for certain transactions, including auto loans. The move presented a conflict between the state and federal level and has kept dealers open to possible legal action over e-contracts in the state.

Earlier this year, some California lawmakers—backed by the auto dealer’s association in the state—set out to change that with AB 380, which would allow e-signatures for auto leases by authorizing dealers to offer prospective buyers the “option of signing their respective contracts and agreements electronically.”

The purpose was simple, said Brian Maas, president of the California New Car Dealers Association: “So there’s no ambiguity under state law anymore.”

“From a trade association standpoint, that’s great, because you can make sure that every deal follows every step the same way,” Maas told Jalopnik. “The problem with a paper contract that’s about 29 inches long, is a lot of consumers go in and they spend maybe a couple hours negotiating over the price of the car, figuring the value of the trade in, deciding what products they’re going to buy… and the last step is they’re going to sign the contract.”

Perhaps, he continued, “The consumer isn’t paying as close attention to all of the disclosures on the contract as they should.” With electronic systems, he argued, consumers are more incentivized and able to review the documents with ease.

Valdez, the attorney in California who represents clients with e-signature issues, vehemently disagreed.

“Cars are usually, for most people, the second biggest investment that they’ll ever make,” he said. “Signing e-contracts further trivializes it. It’s almost like buying something off Amazon.”

Valdez was among a group of attorneys and consumer advocates who pushed back against AB 380.

In a March letter to California lawmakers, Valdez wrote about three Spanish-speaking clients who had “been cheated and defrauded by unscrupulous auto dealers” through e-contracts.

Between their cases, and several past clients, Valdez said they shared a “similar pattern and practice of illicit activity.” Some weren’t provided with a printout of the contract they could review; others weren’t provided with a Spanish translation at any time; later, they learned that terms of their contracts were “different than what was represented to them.”

“The contracts included unwanted add-ons such as service contracts, GAP insurance, and theft deterrent products without the consumers’ consent,” he wrote.

Mass and the auto dealer’s association argued the points raised by Valdez and consumer advocates were a “distraction” to the bill’s purpose.

“This is about an antiquated e-signature statute that’s still on California books, even though federal law preempts it,” he said. “Sure, there’s always going to be instances where folks engage in bad behavior, and we never condone those. If there is in fact a violation, they should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.”

Valdez and consumer advocates argued otherwise, saying it’d only open the floodgate to more issues.

“It would’ve been virtually impossible to prove that you didn’t agree to all of this ridiculous stuff,” said Shahan, the president of Consumers for Auto Reliability and Safety

Ultimately, lawmakers relented and AB 380 was defeated—at least for now. Maas said the dealer’s association was reevaluating whether to push for the legislation again next year. Valdez, for one, still thinks it’s a possibility.

E-contracts could work, he said, “but there was some major problems with this bill.”

Consumer advocates may’ve prevailed in California, but the increased use of e-contracts hasn’t relented elsewhere.

By 2015, Nissan and Infiniti had half of their loan contract volume processed electronically, according to Automotive News. For General Motors, 275 to 300 dealers a month filed electronic retail installment contracts, Automotive News reported at the time. Within two years of launching in 2013, more than 90 percent of Toyota’s dealerships were using e-contracts. Ford’s lending arm said two years back that it offered electronic contracting in all 50 states; today, the “majority” of its contracts are processed electronically.

Among several attorneys and consumer advocates who spoke with Jalopnik for this story, each said they’ve seen a sharp rise in the use of e-contracting in the last couple of years.

That rise, they said, has brought along some unsettling cases, which is why the California fight stood out: it was a less of a proxy war over auto dealer animus as it was a clear-cut battle to speak out about some glaring issues that’ve popped up around e-contracting.

At the time of the sale, a salesperson told Criscione—the truck buyer in Connecticut who ended up with a contract he literally did not bargain for—that he’d been approved for a loan from Credit Acceptance Corporation, a subprime lender that has repeatedly faced scrutiny from regulators. Monthly payments would work out to about $430 to $450 per month.

But the allegedly forged contract called for monthly payments of $602, an increase Criscione didn’t learn about until weeks later, when Credit Acceptance deducted that amount from his bank account—about 35 percent higher than the price the salesperson had conveyed at the dealership. Criscione asked Credit Acceptance for a copy of his loan agreement, and saw for the first time the glaring discrepancies.

“He never saw the contract, he never saw a computer screen, never controlled the mouse, never signed anything on a pad,” said attorney Blinn, who represented Criscione in the case.

Credit Acceptance didn’t respond to requests for comment. Both the lender and the dealer were named as defendants in Criscione’s case. Credit Acceptance settled the suit last month, but claims against Atlantic remain pending.

Atlantic’s attorney, Leonard Crone, confirmed to Jalopnik that Atlantic’s no longer open.

“Atlantic denied that allegation,” Crone said in an email. “The company is no longer in business, but it did file three sworn affidavits with court from eye witnesses who saw Criscione sign the necessary documents.”

Atlantic failed to attend a settlement conference last month, records show. Recently, Blinn wrote in a court filing that Atlantic’s counsel advised that “he is not in touch with anyone representing the business” and that the dealer has since shuttered.

“Disreputable dealerships frequently mislead consumers into what the contract terms are,” he said. “And when the terms aren’t printed on paper and given to the consumer, it’s much easier to mislead them on the content of the contract.”

Taub, the Michigan attorney, said there’s pressing issues with e-contracts for auto loans that need to be addressed.

“This takes away any opportunity for a consumer to make an informed decision about credit,” he said. “And the opportunity to do that was limited at best prior to e-signing. Now it’s just completely gone. That’s the whole point.”